NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

How To Glass Without Using The Grid Technique

It’s mid-afternoon. You’re laying on a rock in the sun, crumpling a candy bar wrapper and picking the last bits of ham and cheese from your teeth. You settle in behind the binoculars, but after a while your leg falls asleep. You change positions, go back to glassing. Muffle a cough, drink some water. Glass.

Eventually it seems very clear: there are no animals out there. You’ve looked at this same hillside all day and just know there aren’t any elk hiding behind the bushes. It feels like time to take a nap, or read a book, or pick even smaller pieces of lunch from ever deeper molars.

That’s when it happens. The Grid.

Gridding

Gridding is a brute force technique borrowed from computer processors. It turns the wild, variable landscape into a flat screen of pixels, then uses optics to interrogate each tile for elk. You start by scanning across your field of view, move the glasses down a little, scan across the field of view, move down... Pretty soon your eyes are glazed, or crossing, and you feel a little sick to your stomach when you come out into the big, wide world.

Gridding is not well suited to the human spirit, but most of us have done it, either accidentally or on recommendation. There are those who defend The Grid. They have innovative psychological tricks to keep the eyes from glazing. They suspect that all the great battles are won through brute force. They have killed the biggest, baddest beasts on the planet, and it’s all because of meticulous gridding.

For people who have spent a lot of time hunting the same animals in the same terrain, gridding can work. That’s because it relies mainly on pattern recognition. The more familiar we are with specific patterns — how big an elk looks compared to a wind-stunted limber pine at a certain distance, or how the color of a muddy coat matches sagebrush in afternoon light — the more we’ll perceive at a glance.

No matter how exhaustive our pattern banks, land will always be a folded surface with intricate pathways and potential blindspots, so it’s hard to read it methodically. While the human brain is very good at targeted pattern recognition, it’s relatively poor at diffuse, broad image searching. That is, if we don’t know exactly what we’re looking for, we might scan over an antler tip — or even a whole animal standing out in the open — without registering “elk.” The less familiar we are with the place and the animals, the less effective gridding will be.

A New Approach

Because part of hunting is exploring new territory and ecosystems (and seeing familiar places in new ways,) we have to use different techniques on unfamiliar ground. Here’s a basic approach to getting familiar with the land, what’s on it, and how animals might interact with those features.

Start with a few establishing passes:

- Landform. Scan the whole field of view using your bare eyes, paying attention to the shape of the land. Where are there canyons or draws? Talus? Timber? Where does one land feature obscure another? If it helps, compare what you see to a map or satellite images.

- Landmarks. Choose distinctive markers that define the land’s depth, both for the unaided eye and in the optics. Depending on ranges and magnifications, those landmarks might be as small as a clump of grass or as big as a cliff band. Practice coming in and out of the glasses, keeping track of where on the three-dimensional surface you’re looking.

These global approaches help lock in distinctive aspects of our field of view. The better a sense we get for the three-dimensional land, the more readily we can interpret specific patterns on top of them. Next, we’ll move to more targeted passes:

- Sore thumb. Using your bare eyes, scan your whole field of view for movement or obvious anomalies, then use the glasses to check them more closely. Stick with each image long enough to articulate to yourself what you think it is, then look away before returning to verify.

- High-contrast areas. Focus on skylines, meadows, snowfields — anywhere that silhouette, color, or shape will pop against the background.

While these techniques involve repeated passes over the landscape, they are methods of targeted search, not mindless gridding. We might read back and forth over a little patch of brush — left to right, right to left, up and down, look away, check it again — just to check whether that darker, horizontal line is a fallen tree or an animal’s back. We never settle in to glare down every last pixel in the world.

Really, these methods just supply raw material for our most powerful search engine — empathy.

Homo sapiens and hunting evolved together. Our eyes and ears have evolved to pinpoint stimuli in three dimensions. Our legs and feet have evolved to get us there quickly and quietly. Most importantly, we have learned to cast our consciousness into other beings, anticipating their desires, aversions, and potential actions. Compassion, not raw intelligence or even tool use, is our greatest strength when it comes to locating and understanding other creatures.

Empathetic Glassing

Compassion makes all the difference during the afternoon lull, when it seems clear that there aren’t any animals around for miles. Empathetic glassing allows us to feel with another being, in order to better understand their motivations and tendencies. To access an animal’s consciousness, we can start by asking ourselves: “If I were an animal, what would I want to be doing right now?”

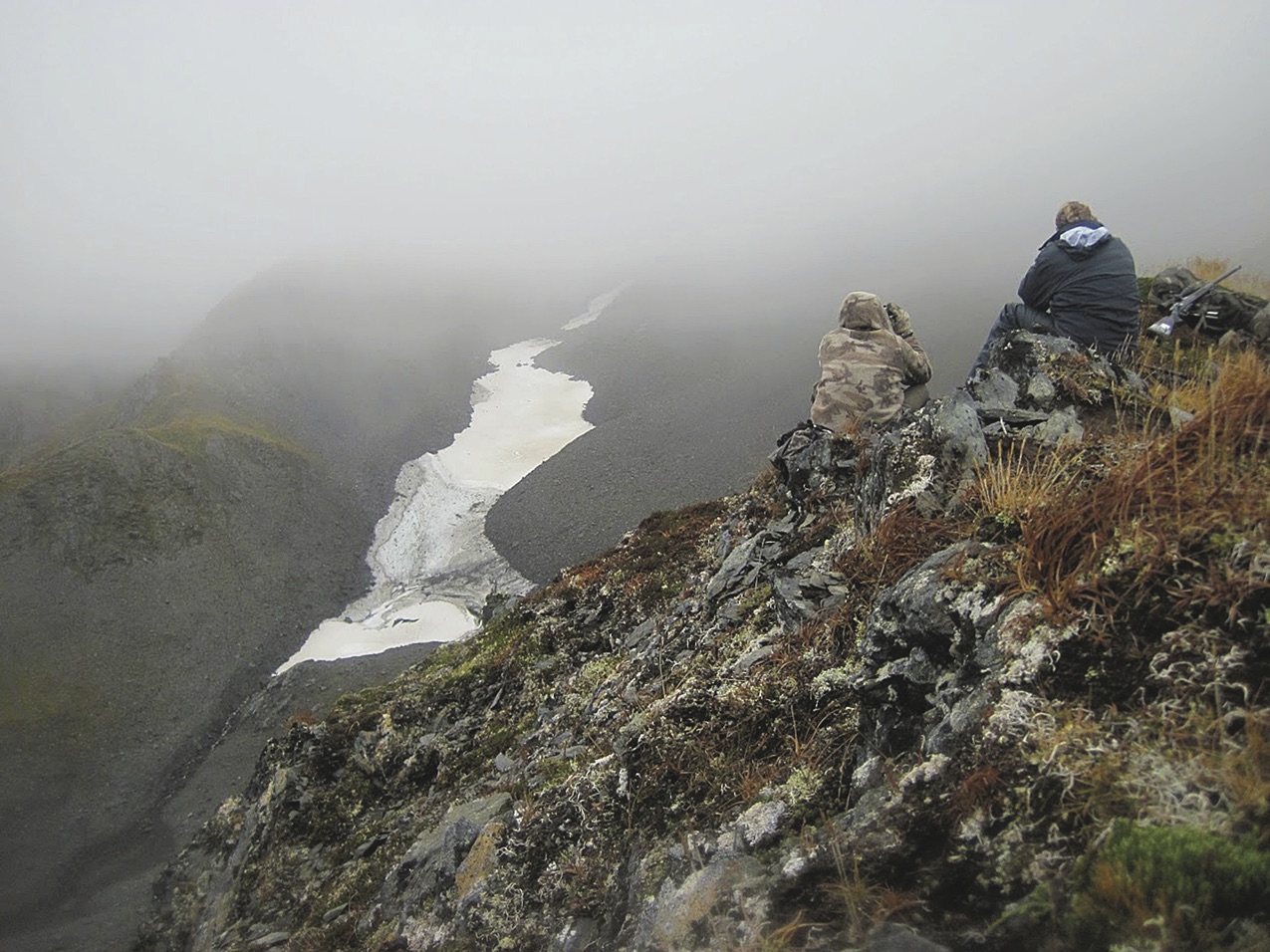

Maybe... I would be staying out of the wind. Or checking on girl animals, getting warm in the sun, cooling off in the snow... or...? By letting our binoculars walk through those possibilities (on the three-dimensional surface established by our initial passes,) we see more of the ecosystem, and see it through an animal’s eyes.

Even if we haven’t spotted any elk, we’ve visualized them in a way that makes us better, more intuitive hunters and trackers. We aren’t looking for animals, exactly, but trying to imagine and predict how we, ourselves, might act in their circumstances. Aligning our identity with the animal (“what would I do?”) lets us bypass the intellectual ego to access instinctive responses — more like what an elk experiences.

Empathy also allows us better anticipate the future. We can ask ourselves what, as elk, we might be doing in two hours, then walk through potential scenarios using the binoculars. We might wonder, “How would I get from that patch of brush down to the creek?” Or, “If I stood from a bed in that timber, I might want to feed into the wind through that opening.” Suddenly the landscape opens itself into nodes linked by pathways. The landmarks we identified earlier now locate corridors of travel, or resting places, or pinch points — all through eyes we’re beginning to share with elk.

The more fully we psychologically merge with another creature, the more physical proximity we can share with them. No amount of computing power or image recognition software can stand in for understanding the creatures and the land we hunt. The empathetic approach allows a deeply personal approach to land and animals, and to understand them in ways that we will never get through gridding.

By Christian Woodward