NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

Maximizing Bowhunting Forgiveness: Part 3

The beauty of stalking mule deer in lush alpine basins in August; the sweet sounds of elk ringing out in the elk woods in September; the buildup of anticipation when twigs snap in the treestand in October; the privilege of chasing mule deer in serene, snow-covered landscapes in November. If you are like me, it’s really hard to pick a favorite season. The beauty of this modern era of hunting is that you don’t have to. There is so much opportunity out there, and you can experience it all if you are willing to branch out. Branching out and experiencing new forms of hunting doesn’t come challenge-free, however. Each one of these different hunting seasons brings new tactics, new challenges, and new gear.

To hit the ground running with the right gear and tactics in a new area, especially with a general archery tag, can be the difference between success and going home empty handed. Success on a public land, DIY bow hunt comes down to the little details. Being a student of the game and taking advantage of the wealth of knowledge shared in Western Hunter Magazine will make you a more versatile hunter. In this article, we’ll go over some of the key factors of a successful archery hunt.

Bowhunting Forgiveness

If you are branching out and going on a new archery hunt this coming fall, this article is perfect to help you be better prepared for your hunt. This article is the third installment in a series I have written discussing “bowhunting forgiveness.” Bowhunting forgiveness essentially means optimizing your bow and arrow for each hunt and season so that it performs and makes up for possible heat-of-the-moment mistakes you may make because of difficult hunting circumstances. There is nothing easy about public land bowhunting out West, and optimizing the forgiveness of your bow and arrow can make all the difference in the world for success in the mountains.

The ultimate goal of a bow hunt is to pierce a big game animal’s lungs with a broadhead, so the single most important thing to fine tune for each hunt is the broadhead delivery system. If you haven’t already read the first two articles in this series, I highly suggest you do so. I’m not talking about generically tuning your bow and arrow in these articles, I’m talking about tips and tricks to specifically tweak your bow and arrow to be better suited for different hunts and seasons.

This third article discusses gear selection, tuning, tips, tricks, and tactics for hunting with multiple arrow designs optimized for your different hunts. The content is perfectly suited for the time of year that this issue is hitting your mailbox. The beginning of the year is a great time to focus on hunt planning, strategy, gear preparation, and gear testing.

Three Primary Arrow Designs

Throughout this archery series, I’ve been talking about my three primary arrow designs that I use, depending on the circumstances of my hunt.

- My long-range arrow weighs 425 grains, travels at 316 FPS, and is designed to have “range forgiveness” for open country hunts.

- My short-range arrow weighs 658 grains and is designed to have “shot-angle forgiveness.”

- My third arrow weighs 525 grains and is built not to exceed 280-290 FPS. I like to use this arrow on hunts where I expect longer-range shots in states that have outlawed mechanical broadheads.

In my experience hunting many western states, these three arrow designs fully cover the multitude of hunting situations present out here. Having these different arrows built and ready to use is only part of the equation, however. The bigger part of the equation is figuring out how to accurately deliver these different arrows through the lungs of a big game animal. This is precisely why throughout this series I have used the term “broadhead delivery system” instead of just saying “arrow.” The arrow is only one part of the equation. The broadhead delivery system consists of the arrow, the bow, and the tune. Short of having three different bows fully set up and tuned to independently shoot each one of these arrow designs, it is not trivial figuring out how to accurately shoot each arrow.

Planning Out Hunting Season

For the last five years, each season, I have used a combination of the three arrow designs listed above. Regardless, deer or elk, I prefer to bow hunt in mostly open terrain, relying on my glass and my stalking skills. Elk on public land and especially in OTC areas are highly pressured. Therefore, the big herd bulls become very, very difficult to call in. For this reason, even for elk, I prefer to hunt mostly open terrain where I can physically see the animals. This means that without fail, every year, I use my long-range arrow build. You could call this my default arrow for the majority of hunting that I do. I encourage you to think about the hunts you routinely do (just as I have explained above) and figure out what characteristics your arrow should have to maximize the forgiveness of your system for that hunt type.

Most every year, I generally use one other arrow design. In 2020, for example, the big buck that I dedicated my season to lived in deep, dark timber throughout the summer and fall. During the entire early season, I would mostly carry my heavy, short-range arrow in the quiver because I was mostly hunting from a treestand and ground blind. Once the rut came in mid-November, the big buck moved out of the dark timber and into more open terrain. At this point, I focused more on my lightweight, long-range arrow setup. I ended up killing this buck in open terrain with my long-range arrow.

In 2021, I got a new bow, the Hoyt RX5, and built up completely new arrows for it. For the fall of 2021, I made plans to bow hunt mostly open terrain, so the first arrow that I built was my tried-and-true, long-range arrow. I made plans to bow hunt deer and elk in Utah in mostly open terrain, elk in Colorado above timberline (very open), and late-season mule deer in open, sage country in Idaho. For my second arrow, I decided that instead of building my normal, short-range arrow, I would be better off designing an arrow that catered to my late-season mule deer hunt in Idaho (Idaho requires fixed blade broadheads). I talked about this arrow build at the end of the second article; it weighs 525 grains and is very forgiving when shooting fixed-blade broadheads at extended ranges.

Preparing For the Worst

One thing that I’ve wanted to bring up in this series is the importance of a backup bow. I think owning and maintaining a backup bow is extremely important. To illustrate the importance of maintaining a backup bow, I will relate a story from my 2020 hunt chasing that big buck.

One evening, in the final stretch of the hunt, I saw “KK” move into an area where I had some game cameras and a ground blind in a funnel point. I was very excited hiking out that night because I figured I would have a good chance of killing the buck the next day. It was late November, and a cyclic freeze/thaw pattern had developed in the weather. It froze hard that night, and to my horror, I slipped on the ice going out and broke a bracket on my bow sight. Instead of being able to hunt KK the next day, I spent all day fixing my bow sight and re-sighting in.

The following day, after having fixed my bow sight, I went back up to hunt. I checked the game cameras in the pinch point and discovered that KK and his does had crossed through that funnel point, a mere 30 yards from my blind, four times throughout that day. That was an absolute gut-puncher. I’ve owned a backup bow every year since 2016 for this exact reason but, like an idiot, I sold my backup in the spring of 2020 to finance other gear. At the time, I thought I had blown my only chance of killing KK simply because of the stupidity of selling my backup bow. The story turned out fine because I ended up killing the buck but, nevertheless, lesson learned; I will never again go into another season without a backup bow.

Shooting Multiple Arrow Designs – Option 1

Maintaining a backup bow can not only save your bacon in situations like I described above, but it also presents the easiest solution for accurately shooting two different arrow builds. Without a doubt, the easiest way to hunt with multiple arrows is to have two different bows (a main bow and a backup), each tuned to shoot a different arrow design. With both setups at the ready, it simply comes down to deciding which bow and arrow combination is most suited for a particular hunt. This is no different than the serious rifle hunter, one who owns multiple rifles, selecting the most appropriate rifle and caliber for a specific hunt. This is a very common occurrence in the rifle hunting world.

In 2021, I ordered one RX5 for my main bow, tuned it for my long-range arrow, and liked it so much that I ordered a second RX5 for my backup bow. I tuned my backup bow to shoot my 525-grain arrow, which is designed for hunting open country with fixed-blade broadheads. Your backup bow doesn’t need to be the same make and model as your main bow but, ideally, it should be similar in feel so your shot execution is similar. The downside to this two-arrow/two-bow solution is cost.

It is not cheap owning two bows and quality accessories for both. However, the benefits of owning and maintaining a backup bow are substantial. Instead of upgrading your bow and accessories every single year, which is very expensive, even if you get top dollar resale value, consider using that extra cash to invest in a second bow setup. I believe you will be much better off in the long run. You’ll be more accurate shooting the same bow for multiple years, you’ll have a backup bow for when shit hits the fan, and you’ll have an easy way to shoot a second arrow design that is better suited for different hunts.

Shooting Multiple Arrow Designs – Option 2

The second option for shooting multiple arrow designs involves a single bow, is more budget-friendly, and doesn’t require a Ph.D. in bow tuning to accomplish. Inherently, different arrow designs react differently when shot through a bow. To account for this, the bow needs to be set up or tuned for each arrow. As I said in the first article, this series assumes that the reader has a moderate to advanced level of understanding of archery and how to tune a bow. Concepts like paper tuning, bare-shaft tuning, or broadhead tuning will not be discussed in depth. If your two arrow builds are designed appropriately to result in a similar dynamic spine (more on this in the section below), the difference in the bow tune from one arrow to the other will be minor. What I mean by this is, if your two arrow designs have a similar dynamic spine, then the arrow rest on your bow may only need to be tweaked slightly to achieve a bullet hole through paper for each arrow.

Well before the hunting season begins (right now in the winter is a perfect time), you should build up your two arrow designs and get them tuned to your bow. How I like to do this is first pick my default arrow and get my bow tuned perfectly around that arrow. I set my arrow rest to a horizontal center shot and start tuning first by making adjustments to the cam spacing and alignment. Depending on your bow, this may be yoke tuning, top hat shimming, spacer shimming, etc. Any minor adjustments needed after that can be accomplished by tweaking the arrow rest in small increments. Once that arrow is tuned to your liking, mark the arrow rest so that you can easily go back to that exact position.

Most arrow rests are aluminum, so it’s pretty easy to use a razor blade to make a very small but permanent mark on the rest, indicating where your default arrow is perfectly tuned. The next step is to tune your secondary arrow, but instead of making changes to the cam alignment, first, make adjustments to the arrow rest. If you have designed your arrow builds so they spine out consistently, then it should only take a minor tweak (likely less than 1/8th of an inch) to get that arrow to tune. If it takes more than 1/8th of an inch, then you will likely need to make some cam alignment tweaks.

Whatever you do, if you have to adjust cam alignment, make sure you document well what you did, so that you can undo those same steps later. Once that arrow is tuned, mark the rest (or make notes regarding changes to cam alignment). The concept here is that, having done this work in the off-season, you can now very easily (and very repeatably) toggle between a perfectly-tuned default arrow and a perfectly-tuned secondary arrow in a matter of minutes at home or in your shop during the hunting season. This is something that can easily be accomplished in a matter of minutes in between hunts.

The next step after tuning both arrow designs is sighting in. The arrows will have significantly different trajectories. The light and fast arrow will have a flat trajectory versus the significant drop of the heavy, short-range arrow. The easiest way to sight in these different arrows is to have two different sights that mount on the bow via a dovetail mount (it also works very well with Hoyt’s new Picatinny attachment). Dovetail or Picatinny attachments make for very repeatable sight installation, so it’s best to use a mounting system like one of these if you plan to take the sight off frequently. From here, it’s pretty straightforward sighting in each sight for each arrow. Just as you need to toggle between arrow rest positions to switch arrows between hunts, you will also toggle between the two sights.

Best Tools for the Job

There are two bow sights on the market right now that I am extremely impressed with in terms of their adaptability for use with multiple arrows. Those sights are the HHA Tetra Max and the digital Garmin Xero A1i and A1i Pro. Both bow sights are extremely modular and can easily handle multiple arrow trajectories in a single unit. In addition to their modularity, I think both these sights are among the top sights in the industry in terms of features and functionality. Writing this at the end of the 2021 bow season, I have put both bow sights through the wringer this year and am very impressed with both.

HHA Tetra Max Bow Sight

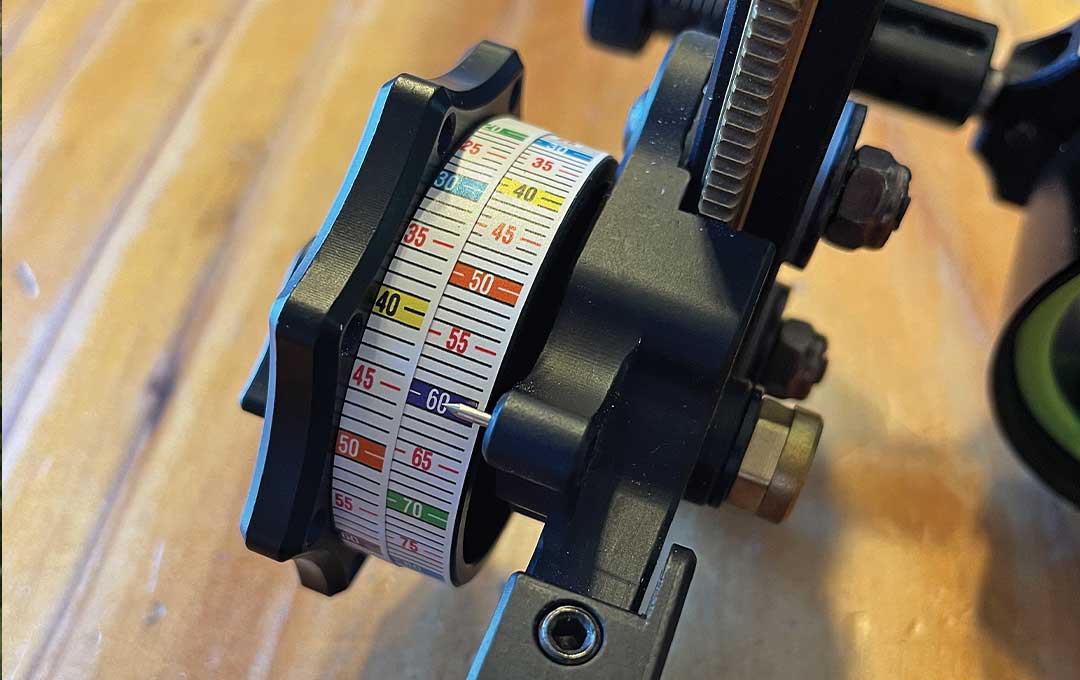

The Tetra Max is HHA’s top-of-the-line slider bow sight. It’s a fantastic sight that strikes the perfect balance between tough-as-nails, feature-rich, and lightweight. Its noteworthy features include first, second, and third axis adjustment; durable and bright pins with brightness control; geared slider drive (no drive stripping or drive “burnout,” which has been a problem for me in the past with other sights); magnified yardage wheel indicator (I really like this); easily interchangeable sight scope heads; and easily interchangeable slider-drive yardage wheels. In fact, the Tetra Max not only has removable/interchangeable yardage wheels but every sight ships with two yardage wheels!

This is directly off of HHA’s website: “Shoot different arrows depending on the season? Every Tetra Max sight includes two yardage wheels, making the switch between [arrow] setups a snap, and not a day on the range.” HHA has designed their Tetra Max model with this two-arrow concept in mind! Between the interchangeable yardage wheels and the easily interchangeable sight scope heads, this sight was made to shoot multiple arrow designs.

I like to shoot three or four-pin slider sights. For my fast arrow setup, I like three pins at 30, 40, and 50 yards. For my heavy arrow setup, I like four pins at 20, 30, 40, and 50 yards. Ultimately, I like to have fixed pins out to 50 yards, regardless of the arrow. Swapping between my different arrow builds in between hunts with the Tetra Max is as easy as loosening a bolt to replace the scope head and loosening a set screw to replace the yardage wheel. It couldn’t be any easier.

HHA Tetra Max $489.99 Buy now on BlackOvis.com

Garmin Xero A1iPro Bow Sight

The newly released Garmin Xero A1iPro is simply an amazing sight. I will be doing a more in-depth review of this sight in a later issue of the Western Hunter, but I’ll explain why I like it for multiple arrows and a few other highlights here. First off, durability was at the forefront of my mind when I first got this sight, and despite it being a digital bow sight, it has been very durable. The features on the Garmin are just outstanding. The first great feature is being able to range at full draw. The Xero is a range-finding bow sight that automatically illuminates a pin for the measured range.

This is an absolute game-changer wherever it is legal to use (a few states don’t allow this kind of bow sight). Oftentimes, the difference between disappointment and successful encounters on trophy animals comes down to seconds, so the ability to eliminate the steps of ranging and scrolling your bow sight is groundbreaking. This feature alone will reduce ranging errors and missed shots and lead to far fewer wounded animals.

Other features that I think are awesome are the digital torque indicator, fixed pin mode, pin brightness control, clean sight picture, and the ability to manage multiple arrow profiles. The digital torque indicator is fantastic. Despite shooting tens of thousands of arrows over the years and feeling very confident with my archery form, this bow sight has helped me become more consistent with my bow grip simply because of the digital torque indicator. You can track if your grip is exactly consistent from shot to shot. The clean sight picture, especially in fixed pin mode, is excellent. Imagine a sight picture with all the benefits of a fixed multi-pin sight without the clutter and obstruction from the actual black pins. There are no physical pins to obstruct your view in this sight’s sight picture, just small, lighted aiming points.

The main reason why I wanted to discuss the Garmin Xero in this article is the multiple arrow profile feature in the A1i and A1iPro models. There simply isn’t a better sight on the market to use for multiple arrows. With a few clicks of a button, you can toggle between different arrow profiles – that’s it. Sight in each of your arrow designs on separate arrow profiles, save those profiles, and then toggle between those profiles as you swap between arrows for different hunts. The Xero is very intuitive to use (especially the new A1iPro with its micro-adjustability). It’s so quick and easy to use that I can toggle between arrow design profiles in a matter of a second, mid-stalk!

Garmin A1i Pro $1299.99 Buy now on BlackOvis.com

Garmin A1i $999.99 Buy now on BlackOvis.com

Shooting Multiple Arrow Designs – Option 3

Switching arrows mid-stalk is the concept that leads me to the final option for shooting multiple arrow designs. The idea behind this option is similar to the second option described above but takes it one step further. It is possible, if you meticulously design your arrows, to get two different arrow designs to tune at the same arrow rest and cam/yoke settings. This means that you won’t need to adjust your tune to swap between your arrow designs. As long as you have a way to track the trajectory of each arrow with your bow sight (more on this later), you can carry both arrow designs in your quiver and quickly select the arrow that is most ideal for the shooting situation while in the field!

I think of this as the pinnacle option for shooting multiple arrow designs. However, the reason why I have listed this option last is that it can be very difficult to accomplish. Getting two vastly different arrow designs to tune to the same settings can be quite challenging. Despite this requiring a lot of work to accomplish during the offseason, I think it’s worth the effort because it offers a groundbreaking amount of flexibility to be able to carry multiple arrow designs in your quiver and have the best of both worlds – a flat trajectory and bone-splitting momentum – at your fingertips.

It takes quite a bit of trial and error playing with different shafts, spines, arrow lengths, point weights, nock-end weights, arrow rest plunger tensions, etc, to get both arrows to tune together. The very first step toward accomplishing this is building out test arrow profiles using archery software like Archer’s Advantage. Within Archer’s Advantage, you enter in all your bow information and arrow build information. Archer’s Advantage will then calculate and plot the dynamic spine of that arrow design in relation to the bow specifications that were entered. It’s pretty neat software that I use all the time for spine tuning and custom sight tapes.

Use Archer’s Advantage to get your different virtual arrow builds to yield approximately the same dynamic spine. The main concepts to keep in mind when working toward this are as follows:

- Adding point weight will decrease dynamic spine stiffness.

- Shortening the arrow will increase dynamic spine stiffness.

- Adding nock-end weight will increase dynamic spine stiffness (wraps, heavier vanes, more vanes, etc).

Your two arrow designs will likely require one or even two size differences in spine. Additionally, for a hunting arrow, I’ve had a great experience staying on the stiff side of optimal spine. In the Archer’s Advantage program, I like to be in the yellow region of the spine plot or “marginally stiff.” I tweak the design of both arrows until I like the arrow speeds and weights and both arrows ideally spine-out “marginally stiff.”

Easton Arrows

From here, the process moves to actually building the different arrows. I like to use Easton shafts for a few reasons. The main reason is that they are very consistent in spine from shaft to shaft. Additionally, Easton shafts do not have a prominent spine line, which means they have more consistent circumferential spine. This translates to less time nock tuning to get arrows to tune together. The second reason is that Easton shafts are made by “pultrusion,” meaning that the ends of the arrow are not prone to wobbling like arrows that are made by the wrap-and-roll process.

Building and Tuning the First Arrow Design

To start building, I typically cut a little off the insert end of the arrow, and then square it with a G5 arrow squaring tool. I then insert the arrow with the appropriate amount of insert weight. My favorite component system on the market for micro-diameter arrows is the Ironwill Outfitter system. The inserts are H.I.T. inserts that fit up inside the shaft. This system is very versatile because it comes in a variety of weight options and you can also double-stack inserts in the shaft. I like to add more insert weight (up inside the shaft) than broadhead weight.

If you are adding a lot of weight up front and are running into spine problems, adding insert weight into the shaft can help remedy this, somewhat. When adding point weight into the shaft instead of out in front with a bigger broadhead, you are changing the center of mass of the front of the arrow. You are shifting the center of mass backward, which effectively increases the spine of the arrow.

Once the arrow is inserted, I leave the arrow long and start shooting bare shafts through paper. I start this process with the arrow rest at a reasonable center shot (13/16” to 7/8”) and with reasonable cam alignment on the bow. After shooting and seeing the paper tear, I remove the nock and cut the arrow from the back end a half-inch at a time until I start to see the paper tear resolve. After a few iterations, as I am zeroing in on the tune, I start cutting off a quarter-inch at a time. I continue this process until the arrow shoots a perfect bare shaft bullet hole. It’s certainly okay to tweak the arrow rest position or cam alignment slightly to bring the arrow into tune at the desired shaft length. Be prudent here, as I don’t recommend going too far from the standard bow center shot.

Tuning the Second Arrow Design

The next step is tuning the second arrow design. Leave the arrow rest and cam alignment settings the same as with the first arrow. After the arrow is inserted, start shooting it through paper, cutting off the back end of the shaft as necessary to bring it into tune. You may get this second arrow close but not perfectly tuned by this method alone. If it’s tearing more than a quarter-inch at about 10 feet, then you will need to start some trial-and-error tinkering. The goal of the tinkering is to get both arrows to react the same way when shot through paper.

The first thing to test is the arrow rest plunger tension. Try increasing and decreasing the plunger tension. Further tinkering can include adding or removing point weight on either arrow (try different collar weights, collar on/collar off, and different field tip weights); wrapping electrical tape around the backend of either arrow to stiffen it up (the electrical tape simulates weight on the back of the arrow from vanes, wraps, etc); and nock tuning (rotating the nock of the arrow will slightly change the paper tear). As you tinker and make changes to the system (cam alignment, arrow rest, plunger tension, point weight, nock-end weight, etc), make sure to go back and shoot the first arrow to see how it reacts to the changes. Eventually, after enough tinkering, you should be able to get both arrows to react about the same through paper.

Deciding Precedence

One of the most important aspects of all of this is to give precedence to and perfectly tune the arrow you have designed to shoot fixed blade broadheads. When shooting multiple arrow designs, if one is tipped with a fixed blade and one is tipped with a mechanical, it is far more important to get the fixed-blade arrow tuned perfectly. Depending on your setup, it may be difficult to get both arrows to shoot perfect bullet holes, but that’s okay as long as the arrow that isn’t perfect is shooting a mechanical. As long as the tune is close, an arrow tipped with a low-profile mechanical (like the Sevr) will self-correct very quickly out of the bow (will not experience major tuning-related drift downrange). If the mechanical-broadhead arrow is tearing less than a quarter-inch through paper, then the tune is probably good enough. If you are a perfectionist and just need both arrows to tune perfectly, be prepared to do A LOT of tinkering!

One last thing to note about tuning between the two different arrow builds is the orientation of the paper tear. If the difference between your perfectly tuned arrow (the one that will be tipped with a fixed blade) and the mechanical arrow is a small vertical tear (say less than a half-inch at 10 ft), then that is not a big deal, especially if the mechanical arrow is tearing nock-high. If you can’t resolve a small vertical tear from the mechanical arrow but the fixed-blade arrow yields a perfect bullet hole, that is completely okay. Horizontal paper tears are the ones that should be resolved to ideally less than a quarter-inch.

Two Arrow Trajectories in One Bow Sight

The two different arrow designs in option three will have vastly different trajectories that need to be accounted for with the bow sight except, here in option three, it’s not feasible to change out your bow sight mid-stalk, so, you need to be able to account for two different arrow trajectories with a single bow sight. The first and easiest option was already discussed above. Both the Garmin Xero A1i and A1iPro models have a multiple arrow profile feature that will allow you to toggle between different arrow profiles in about a second by pressing a couple of buttons. Mid-stalk, if you see that you are going to be presented with a close-range, frontal shot, you can nock your heavy arrow (as opposed to your light/fast arrow), press a few buttons on your sight to change the arrow profile, and you are good to go.

Before using the Garmin, I was able to accomplish this task in a few different ways, depending on the sight that I was using at the time. As I have said before, I prefer multi-pin slider sights – typically, three or four pins. Multi-pin sights are more versatile for use with multiple arrow designs. I typically set up my sight such that my pins are positioned to yield 30, 40, 50, and 60 yards with my fast, lightweight arrow. It just so happens with my bow setup that these pins (without moving them) correspond pretty closely to 20, 29, 37, and 45 yards. To figure this out, I get my pins set exactly where I want them to be with my primary arrow (for me, that’s my light and fast arrow). I then walk the archery range, shooting my heavy arrow at different yardages to figure out exactly where those previously set pins correspond with the heavy arrow. Most years, I am satisfied with this setup as-is. I have fixed pins out to 60 yards for my lightweight arrow and fixed pins out to 45 yards for the heavy arrow.

Inherently, I always set up my sight tape and slider portion of my sight to correspond to my lightweight, long-range arrow. In the past, I have set up a second sight tape on the backside of my sight, corresponding to the heavy arrow. Whereas the main sight tape for my light arrow starts at 60 yards, the heavy arrow sight tape starts at 45 yards. This allows me to dial to yardages beyond my bottom pin, even with my heavy arrow. I was able to do this previously on a Black Gold Pure Gold sight, but it is also possible to place a second tape offset to the side of the main sight tape on the HHA Tetra Max yardage wheel.

In practice, you need to be on top of your game and fully in the details to hunt with multiple arrow designs in your quiver. I recommend fletching the different arrows with different color vanes as a clear arrow indicator. Whenever I am in a stalking situation and I nock an arrow, I consciously state in my mind, over and over again, what my pins are set for, for that arrow. If the lightweight arrow is nocked, I think, 30, 40, 50, 60… If the heavy arrow is nocked, I think, 20, 29, 37, 45 repeatedly. I’ve never screwed this up in the field because it’s ALWAYS at the forefront of my mind.

Only as Good as the Weak Link

All of this attention to detail with the arrows; all of the talk about accuracy and forgiveness; all of the time that goes into your bow and the tune; are only as good as the weak link in your system. Hunting out West, bowhunters are often faced with long, steep shots that require accurate ballistic solutions to land an arrow in the kill zone. Most rangefinders on the market use the rifleman’s rule to determine the ballistic solution for steep shots. It’s performing a math function – cosine of the angle of inclination multiplied by the line-of-sight distance – to determine the horizontal component of distance.

Using the rifleman’s rule, you shoot for the horizontal component of distance only. This is a decent approximation, but if you have ever shot at a steep-mountain 3D shoot, you’ve probably noticed that during those long, steep shots, your rangefinder isn’t delivering as accurate of ballistic solutions. The longer and steeper the shot, the more error is introduced, using the rifleman’s rule. On long, steep shots, there is enough error with the rifleman’s rule that it’s very possible to wound or flat-out miss an animal because of a bad range estimate.

Leupold RX-Fulldraw 4 Rangefinder

Throughout this series, I have briefly mentioned the new Leupold RX-Fulldraw 4 rangefinder. The RX-Fulldraw 4 is the first truly archery-specific rangefinder available, and I think it’s a game-changer for accuracy and forgiveness. This is the first rangefinder to use archery-specific inputs like arrow weight, arrow initial velocity, and peep height to calculate more accurate ballistic solutions for steep shots. It’s taking the science of ballistics that is heavily used in long-range rifle shooting and applying it to archery.

Based on my experience using the RX-Fulldraw 4 at Total Archery Challenge at Snowbird and throughout the 2021 archery season, this rangefinder delivers substantially more accurate ballistic solutions than any other rangefinder I’ve ever used, and it’s very intuitive to use. To get ballistic solutions this accurate before, guys were developing handmade cut charts and, based on the shot angle, would have to cross-reference this chart before dialing for the distance. The RX-Fulldraw 4 does all these calculations in a fraction of a second and yields a ballistic solution almost instantly. The full draw 4 is no longer available check out the Leupold 5 RX-Fulldraw Rangefinder.

Leupold RX-Fulldraw 5 Rangefinder $399 Buy now on Outdoorsmans.com

Conclusion

The intent of this series of articles is to inspire you, the reader, to think more about and become more aware of the clear advantages that different arrow designs can promote in the hunts that YOU do. If a bowhunter goes into the field with an arrow optimized for his/her specific hunt, it’s a distinct advantage that can directly lead to a trophy at the end of the blood. If the entire goal of the hunt is to pierce the lungs of a big game animal, there is nothing more important to fine-tune than the broadhead delivery system. I would not have had the success I have had if it weren’t for my methodical approach to engineering my broadhead delivery system. I know my system has helped me kill animals that I would have otherwise not killed due to heat-of-the-moment mistakes on my part.

The pinnacle of “bowhunting forgiveness” is setting up your broadhead delivery system to simultaneously shoot different arrow designs. This will allow you, the bowhunter, to have the best of both worlds – flat trajectory and bone-splitting momentum – at your fingertips. I can’t think of a greater advantage to take into the field as a bowhunter.