NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

Making the Case for a Good Tracking Dog

After completing almost 80 laps around the sun, I have been classified as a senior citizen by many of my peers and most certainly by my current hunting partners who are not even half my age. As we hunt, pack our horses and mules and climb the mountains together, I am constantly reminded of how much hunting has changed over the years.

When I began my apprenticeship as a young hunter, hunting with my brother and father, there was no camo other than what you found in the Army Surplus stores, army surplus jeeps were considered the real deal for those who had them, our neighbor had a “wind sled” which he built himself, hunters who came to our farm to hunt from Seattle wore red and black plaid shirts and wool pants, and their ’06 rifles and gear smelled like Hoppe’s #9. I could go on and on about all of the changes I have experienced, but the one thing that has not changed when it comes to hunting is the wounding loss of big game.

Hunting season was always a time when hunters came to our farm as well as our neighbors’ farm for the opening weekend. I have many wonderful memories of these hunters and these times, but the ones that stick in my mind are the hunters who made marginal shots on mule deer and ended up chasing the deer onto our property, encountering another hunter who had killed the wounded deer and the ensuing fights/arguments that occurred over possession of the deer, or not finding the deer at all. Hunters talked about observing other hunters taking “pot shots” across the canyon, wounding game. Other hunters talked about “losing a buck” and seemed to accept it as a normal aspect of hunting.

Much later, when archery seasons were established and compound bows were developed, resulting in a lot more novice bowhunters, I was puzzled by those who seemed compelled to tell me about the bull elk they “stuck” and lost. It was almost like hitting one was almost as good as killing and retrieving one. Since those days more than three decades ago, I have pondered the issue and have wounded and lost two bull elk myself. One of these took place in the Idaho backcountry with a modern rifle and a shot that I should not have taken; the other I shot with a muzzleloader and blood-trailed to where it went on to private property where I did not have access in Colorado.

Those two experiences have bothered me for years as I have thought about this issue. It is an issue that is often recognized by hunters but never really examined or discussed as to its cause or available remedies.

Thus, it was one of those “aha” moments a couple of weeks ago when my hunting partner, Tyler Weimerskirch, and I were sitting in camp in Idaho’s backcountry, waiting out the fog when he told me about the pronghorn buck he shot with his bow in Wyoming earlier this fall. Although the shot was lethal, the pronghorn buck ran a few hundred yards before he recovered it. After he shot his buck and it ran off, his hunting partner, Mike Kentner, went back to the truck and got “Tracker,” his Jagdterrier, out of the truck, put it on a leash, and took it to where the pronghorn had been shot. Tracker followed the pronghorn’s trail and in just a few minutes found it where it died. He said he was amazed at how excited the dog was and how precisely he followed the pronghorn’s track through the sage and around the hill to where the buck died.

Like many other hunters, I have trained and hunted with bird dogs all of my life. I have hunted mountain lions and bears with dogs, but I have never given blood tracking dogs much thought. . . at least until Tyler and Mike opened my eyes to this great new experience. After our Idaho hunt, I learned that my neighbors, Chris and Kim Blaskowski, have had tracking dogs for years and live only three miles from me. Chris and Kim are good examples of how little we hunters out west know about tracking dogs or their use and efficiency for finding wounded game. As it turns out, these dogs are a truly great asset to hunters who have them and those hunters who ask for help tracking wounded game.

Culture and Traditions: East vs West, North vs South

Years ago, I was in South Carolina during deer season and was amazed at the numbers of hunters whom I saw along the highways who were out with their dogs, chasing whitetail deer. As we traveled through the area, my friend related to me how hunting deer, hogs, and the like with dogs is engrained in the southern culture – so it is with blood-tracking dogs. Throughout the southern and eastern parts of the US, blood-tracking dogs are very much the norm. Out here in the West, we hunt mountain lions, bears, ducks, geese, and upland birds with dogs, but seldom even recognize the value of using a blood-tracking dog for big game.

Many big game hunters in the West frown upon the use of a dog and even believe it may be unethical or illegal. I have hunted upland game all of my life and the thought of hunting upland birds without my dogs is a very foreign concept to me. My dogs are my hunting partners, my friends, and my constant companions. I share their excitement when we are getting ready to go hunting and especially when we are out somewhere in the field and they make a great find, fetch, or whatever.

When it comes to hunting in the backcountry for deer or elk, my relationship with my horses and mules is nearly the same. They share my excitement of being in the mountains and I have often said that for me, hunting in the backcountry without my horses and mules is like hunting birds without my dogs. When one considers the advantages of using a blood-tracking dog for retrieval of wounded game and observes such a dog in action, there is no question as to the value of this practice and instead of it being unethical, some hunters with tracking dogs believe it is almost unethical to not have a dog help with the retrieval of wounded game.

The Dogs

Although many different hound breeds are capable of being trained and used for blood tracking wounded game, those breeds with German ancestry are the most preferred. These breeds range from the Teckel, which is a wire-haired Dachshund, to the Jagdterrier to the Deutsch-Drahthaar which is the product of German history dating back to the 19th century. The Germans who developed these dogs put a lot of emphasis on the idea of a versatile breed. In the late 19th century, a group of breeders set out to create a dog that could fulfill all the aspects of hunting with a dog, from forest to field to water, and could be used on foot rather than by horseback. If you want to start a fight, just call someone’s Deutsch-Drahthaar a wirehair. I know, as I’ve done it before by accident, and it led me to want to understand the difference. For this article, I have used examples of the Teckel, Jagdterrier, and the Deutsch-Drahthaar.

When selecting a dog for blood tracking the following characteristics are important to consider:

⦁ Intelligence

⦁ Nose

⦁ Desire to track

⦁ Trainability

⦁ Responsiveness

⦁ Stability and courage

⦁ Endurance and physical toughness

⦁ Temperament/Demeanor

Before you buy a dog:

⦁ Do not go out and spend $5,000 on a puppy.

⦁ Do your research.

⦁ Get on the Blood Tracking Association website (⦁ unitedbloodtrackers.org) and learn as much as you can about blood tracking dogs, techniques, and the like. United Blood Trackers is “dedicated to promoting resource conservation through the use of trained tracking dogs in the ethical recovery of big game.” UBT has a wonderful group of people dedicated to serving hunters. They provide tracking dogs and help train others in the fine art of using them. It is also the UBT mission to promote the legalization of tracking dogs in all 50 states.

⦁ Obtain a copy of John Jeanneney’s Tracking Dogs for Finding Wounded Deer (Teckel Time Inc. Berne, NY ⦁ born-to-track.com)

⦁ Find someone who has a tracking dog and accompany them in the field so you can see how effective these dogs are.

⦁ Ask questions until you are confident you know what breed of dog you would like.

⦁ When you are ready, begin visiting and interviewing breeders in your area.

Change is Coming to the West

As a result of a lot of great work and outreach by United Blood Trackers, the practice of using blood tracking dogs is being introduced and accepted by the Fish and Game departments of many western states. The United Blood Tackers’ “ambassadors” have put on demonstrations throughout the West, and, year after year, more and more western states are incorporating blood tracking with leashed dogs into their game laws.

Although trained blood tracking dogs can be trained to track off-leash, a technique called “Bringsel,” game departments choose the on-leash practice. With this practice, there is a great deal more control of the dog by its handler, and they don’t have to be concerned about individuals who have random, untrained dogs running loose in the woods during hunting season, claiming they are trained blood tracking dogs. Thus, the Bringsel method of tracking a wounded big game animal is not legal in most Western states.

The Bringsel method was perfected years ago during the two world wars where dogs were trained and used on the battlefield to find wounded and dead soldiers. The tracking dog has a strap attached to its collar and is sent out on a scent trail with no leash. When the dog finds the animal it is tracking, it holds the strap in its mouth and returns to its handler, indicating the dog has found the deer or whatever it is tracking. The handler then follows the dog back to its find.

Montana’s Tracking Dog Law

Since each state has its own unique rules for the use of dogs for tracking wounded game, one should be familiar with these rules before taking a blood tracking dog afield. Montana’s law is a good example and includes the majority of the key elements of these laws.

On April 22, 2011, Montana Senate Bill 135 allowing the use of dogs to track wounded game (and carrying firearms during such tracking) was signed by the Governor. The text of the relevant section reads: (a) A person with a valid hunting license issued pursuant to Title 87, chapter 2, may use a dog to track a wounded game animal during an appropriate open season. Any person using a dog in this manner: (i) shall maintain physical control of the dog at all times by means of a maximum 50-foot lead attached to the dog’s collar or harness; (ii) during the general season, whether handling or accompanying the dog, shall wear hunter orange material pursuant to 87-3-302; (iii) may carry any weapon allowed by law; (iv) may dispose of the wounded game animal using any weapon allowed by the valid hunting license; and (v) shall immediately tag an animal that has been reduced to possession in accordance with 87-2-509. (b) Dog handlers tracking a wounded game animal with a dog are exempt from licensing requirements under Title 87, chapter 2, as long as they are accompanied by the licensed hunter who wounded the game animal.”

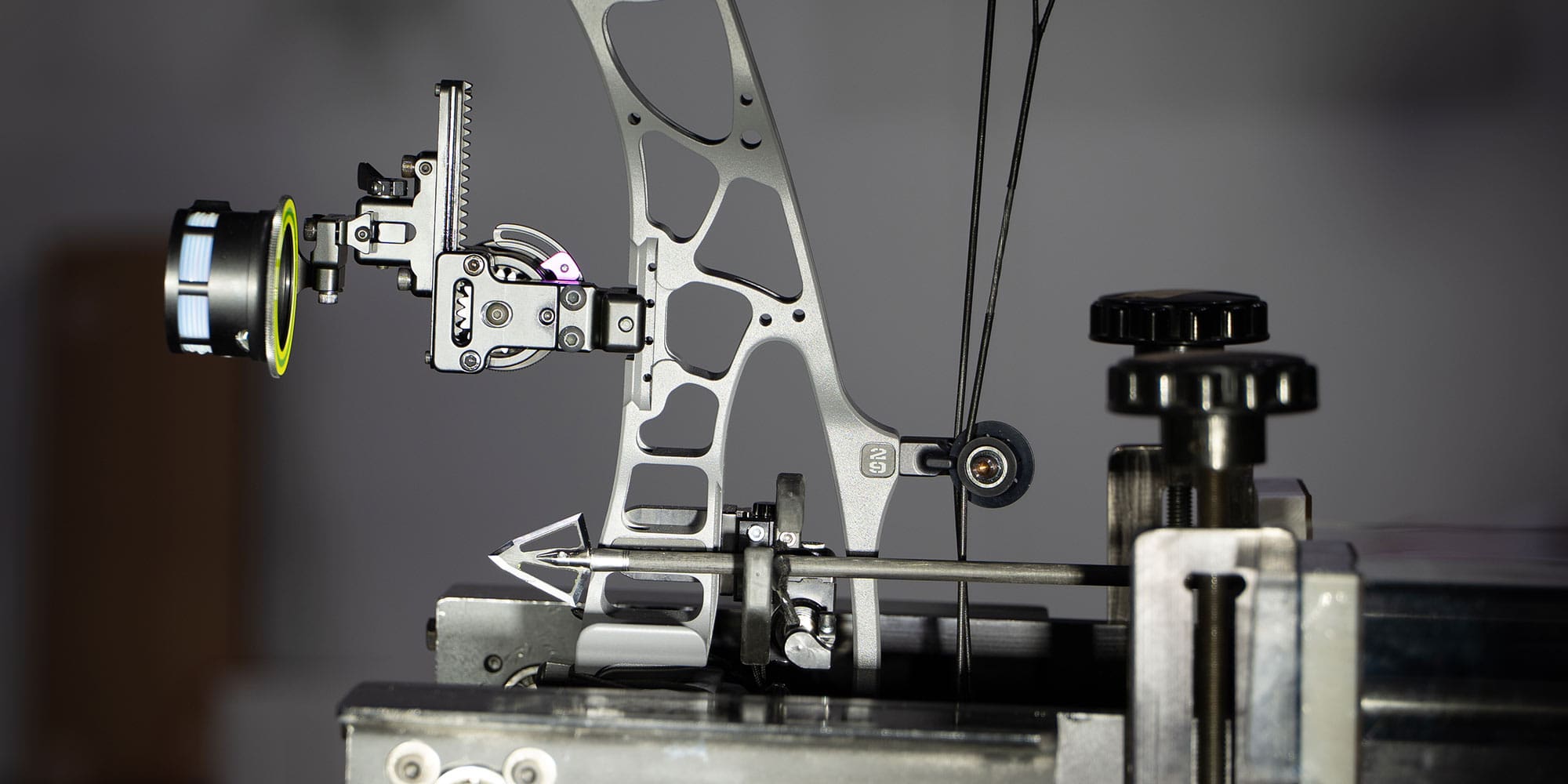

Tracking Tools of the Trade

- The Dog: This one is a 6-month-old Deutsch Drahthaar named Briar that belongs to Chris and Kim Blaskowski, Stevensville, MT.

- The Tracking Collar: A wider than normal collar that allows the dog to pull some without cutting the skin or air supply. Also, note how the lead is tucked below the dog's front leg. This further protects the dogs breathing by applying pressure to the back of the neck rather than the throat. A harness is often used for smaller dogs to achieve the same goal.

- The Long Lead: These come in a variety of lengths and materials. High visibility colors make it easier to avoid stepping on and untangle snags. Biothane, the synthetic shown here, is impervious to weather and most brush but leather and waxed rope are also popular.

- The Blood Sponge: This one is on a stick that allows the owner to sponge blood spots from the cup at the far right along a simulated wounded animal trail for off-season training.

- The Blood: Blood collected from a freshly killed game animal can be bottled and frozen for off-season training. When game blood is not available, domestic stock blood such as beef or pork can also be used. Blood can be sponged or dripped out along an artificial line.

- The Hide: Something to find at the end of a practice track that is rewarding to the dog is imperative. If the reward simulates a real track, even better. This bear hide has been tanned for easy storage and transport, but frozen fresh deer skins work well too.

- Tracking Shoes: These are shoes that attach to a normal pair of boots and hold a real deer hoof in the sole to simulate the steps on a wounded deer for training line. Wounded cervids emit a particular scent through the hoof's interdigital gland. Tracking this scent is an important skill for a dog crossing from beginner to advanced, allowing tracking where blood scent has stopped due to clotting or finding the right track out of a scent-heavy area such as an elk shot amongst a herd or a deer at a feeder. Hooves can be cut from harvested animals and frozen for off-season training.

Recovering Wounded Game – Tracking vs Trailing

Dogs used for recovering wounded game are often referred to as “blood trackers” but the term can be misleading. More often than not, blood tracking dogs are used to track when there is little or no blood. Dogs find wounded game by a combination of tracking and trailing. On a wounded animal, a tracking dog does far more than track. It often trails the animal with its nose held high and follows the body scent of the animal. This covers a broad zone of the animal’s path comprised of scent from the tarsal gland and scent particles from the wound.

The dog also “tracks” blood droplets that stay in the precise place on the track line. Blood tracking at its highest level is tracking when there is no blood and the dog follows distinctive individual scents. Rain enhances the scent. In such a case, where there is no visible blood, the dog will run the track in minutes. Trained tracking dogs will also recognize the scent of individual animals and follow their scent through areas where other deer and elk have been without any trouble, much like a trained bloodhound will recognize the scent of a specific person.

Tips and Advice for Hunters

Bow-shot deer and elk are more difficult to track than those shot with a rifle because often, the bleeding on the animal is internal and the wound is sealed by moving layers of muscle or plugged with fat. Little scent comes down from the wound and the edges of the wound tend to close and seal with blood-soaked hair. Rifle wounds, in contrast, leave an open, ragged wound that allows more scent particles to drift down to the ground.

Deer and elk behave differently depending upon the location of the wound. How far the animal will travel and where it will go depends upon the wound and the individual animal. An animal shot in the paunch may walk for miles before it dies. Animals shot above the spine or in the shoulder seldom bleed a great deal externally and may live for weeks and some even survive from the wound. These animals are often not recoverable.

Animals bow shot in the chest may travel a long distance or survive if the arrow does not penetrate the small opening at the center of the chest. The arrow can strike the ribs at a narrow angle and be deflected backward without penetrating the chest cavity. Deer and elk shot in the chest do not know what happened and often will try to return to a secure place. With little external bleeding, these animals are very difficult to find. Generally, bowhunters can give more detailed information about the hit on the animal than rifle hunters because their shots are usually closer, and they see the arrow enter the target.

Before taking a track, it is important for the dog handler to interview the hunter in order to determine whether or not to go out to search for the wounded animal. What has the hunter done after the shot? How long has the hunter waited before pursuing the animal? Where was the hit on the animal? On gut-shot animals, it is important to get the hunter to wait and not bump the deer or especially an elk.

The waiting time on such an animal is longer than normal. When pushed, an animal shot in the paunch may travel three or four miles. Grid searching makes it difficult to track a wounded animal and makes it ten times harder because of all of the human scent and the disturbance of the ground, foliage, etc. in the area.

Most high-back shots above the spine are not recoverable and the animal does not bleed and often will not die. Many hunters, especially rifle hunters, do not know where they hit the animal.

Elk hunters who wound an elk well off the beaten path have the most difficult challenge. They are often hunting several hours back in the mountains, and it takes time for a tracker to get to the location. Elk are tough animals and will travel long distances, even when lethally shot. Hunters often bump wounded elk too soon after a shot, and a wounded bull will often go three to four miles. One lung is not enough. A bull elk will travel a long way with an arrow in only one lung.

If you wound a big game animal:

⦁ Mark the location of your hit.

⦁ Back out and do not push the wounded animal.

⦁ Wait for the dog.

⦁ Give it a few hours before pursuing.

⦁ Let it go and let it die.

⦁ Confidence in the dog is great…the dog knows he will find the animal.

Expectations of Trackers

Trackers will often travel long distances, especially in the South and Eastern US, to track wounded game for hunters. Typically, these trackers do not charge a fee and simply expect help with travel expenses. They are dedicated to their dogs and their respect for the wounded animal surpasses any fees they may charge. Out here in the West, the logistics of tracking, especially on elk in the mountains, are much more complicated, but dedicated trackers will do all they can to assist hunters who have wounded game.

The general advice for hunters from these dedicated trackers it to have the contact for trackers in your area in your phone, inReach or other communication device so if you wound an animal you can contact them and consult with them on the recoverability of the animal, how long to wait, and other key information. Another key factor is to know where you are! GPS coordinates are key – both where you are located and the location of the hit on the animal. Knowledge of private property lines is also very critical in the event a wounded animal goes on to private property.

Why Hunters Get Tracking Dogs

Logan Duke, from Atlanta Georgia, is a judge for UBC. He travels throughout the US each fall with his two Deutsch Drahthaars, helping hunters find wounded game. Logan wanted a dog to fetch and hunt ducks, so he settled on a Deutsch-Drahthaar with the bonus that it was a tracking dog that was legal to use in his home state of Georgia. Logan provided me with much of the information for this article and is a wonderful resource if one is interested in blood-tracking dogs. (logan@buckheadu.com)

Chris and Kim Blaskowski, my neighbors, are no strangers to tracking dogs. Chris, a traditional bowhunter, originally from Wisconsin, dreamed of a tracking dog all of his life. When Chris and his wife, Kim, moved to Montana, he found Cain, a Deutsch-Drahthaar, which he has trained to track wounded game as well as bears and mountain lions. Kim recently acquired Ruby Rose, a Teckel. Their most recent addition is a six-month-old Deutsch Drahthaar named Briar.

Mike Kentner, a very accomplished bow hunter from Riverdale, Wyoming, decided to get a tracking dog because he had lost wounded animals, including a bull elk he hit in the liver and lost after three days of searching. The summer after that experience, he went on a hunt in Africa and hit a kudu in the same place as he had hit his Wyoming bull. The PH’s tracking dog found the Kudu in less than 20 minutes.

When he got home, the Blood Tracking Association was in Wyoming, presenting the merits of blood tracking dogs for finding wounded game to Wyoming Game and Fish officials. Seeing the merits of legalizing such dogs for tracking wounded game, Wyoming Game and Fish legalized leashed tracking dogs. As soon as tracking dogs were legal in Wyoming, Mike did his research and settled on a Jagdterrier which he named “Tracker.” He decided on this breed for several reasons. It was a small, but mighty dog with a great deal of enthusiasm, drive, endurance and a great nose. The bonus was the dog is a great house dog, is great with children, and these dogs make great hunting partners. Tracker goes everywhere with Mike in his truck and will stay in the truck all day long while Mike is hunting, waiting to track for Mike. Mike also takes Tracker to his remote backcountry camps, and Tracker will stay in camp all day long, waiting for Mike to return.

Mike got Tracker as a pup in July, and at 12 weeks old, Tracker was on his first blood trail. By the end of the first season, Tracker had trailed 25 big game animals, many of which could have been recovered without the dog and others that would likely never have been found without the dog. Mike takes Tracker on every kill just to keep him fresh, and Tracker loves every minute of it. The longest successful track was three miles on a mule deer shot in the paunch during archery season! The dog followed the deer’s scent as it walked three miles.

Since he got Tracker, Mike has not lost an animal. When asked about the ethics of using a dog for big game hunting, Mike’s reply is, “It is almost unethical to not use a tracking dog while hunting big game.”