NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

Inside the Chaos and Secrecy Surrounding the Release of 10 Wolves in Colorado

In November 2020, Colorado voters approved Proposition 114 which required the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Department (CPW) to create a plan to reintroduce and manage gray wolves on designated lands west of the Continental Divide by the end of 2023. This proposition sounds innocent and innocuous to the uninformed, rapturous to the wolf-lovers, and highly concerning to hunters and livestock ranchers.

This reintroduction carries weight beyond simply having wolves on the landscape and plays into the culture war currently going on in this country. Additionally, some believe that there is a far greater plan from the national animal activist community to create a ground zero for a seeding population of wolves in the centrally located Colorado. This would provide a spreading and population increase of wolves to seven different states that share a border with Colorado.

History

Finding a starting point to tell this story probably takes us back 20-plus years to when pro-wolf and predator groups actively lobbied Colorado Parks & Wildlife (formerly known as the Colorado Division of Wildlife) at meetings of the CPW Wildlife Commission. There was a desire by some animal activists to have reintroduction plans for grizzlies, wolves, lynx, and wolverines to Colorado. What was decided was that human development and populations in Colorado had expanded to the extent that there would be too many human and livestock conflicts with grizzly bears and wolves, so no plan was initiated. A reintroduction of lynx took place with marginal results, several lynx casualties, and now rare sightings of the animal in areas where the cats were released.

The wolf remained this enigmatic shadow in the backdrop of wildlife management issues that were occasionally discussed and rebuked. It was not until Jared Polis was elected governor of the state of Colorado in 2018 did serious wolf reintroduction discussions started taking place again by government officials. These changes have far-reaching intent and ramifications beyond the simple reintroduction of wolves.

Polis Administration

Governor Jared Polis has a long personal history in politics and was a five-term congressman for Colorado. Nowhere in his personal or political history was there much evidence of wildlife and or animal welfare-related advocacy, so the push toward wolf reintroduction seemed out of his target zone as governor of Colorado. However, Polis’s husband, Marlon Reis, is recognized on the national level as a vegan animal activist whom some call an “extremist,” and he is quite obviously helping to craft policy towards livestock and wildlife in Colorado. “My passion is definitely animal welfare,” said Reis in a 2019 interview. What is very apparent at this point is that there is a very sympathetic person in the governor’s mansion to animal activism and anti-hunting and anti-livestock groups.

Some may shrug off this aspect of wildlife management and policy in Colorado as being a sideshow to many of the other aspects of Polis’s policies. However, hunters, anglers, and ranchers have found out that this is very alarming, and there are active attempts in place to completely change the face of Colorado wildlife management and public lands utilization.

One of Polis’s first consequential acts as the new governor toward hunters and anglers was to completely rebuild the CPW Board of Commissioners. The Commission is an 11-seat board composed of citizens of Colorado that are hand-picked by the governor and sets regulations and policies for Colorado’s wildlife and state parks.

What is very apparent a few short years later is that the makeup of the commission has been crafted as an echo chamber where hunters seemed to have lost a voice and representation. Not only that, current commission members have professional careers entrenched in activism and animal welfare/rights issues. To assume they bring unbiased altruism toward wildlife and sportsmen and women is nothing short of simple ignorance and wishful thinking. There is an agenda in play, and the future of hunting in Colorado for our children and theirs hangs in a precarious place.

Selective Attention

Governor Polis made a public promise to the people of Colorado that wolves would be on the ground in Colorado by the end of 2023. What we have seen is that the opposition to the reintroduction or the concerns about the effects that this will have on the livestock industry are of zero consequence to the governor. So far, lip service and indifference are the only responses given to the opposition. This is especially troubling considering the ballot initiative passed by only around 10,000 votes in a state of nearly six million people and was approved by primarily urban voters with very little skin in the game.

What has been also apparent is that those who drafted the bill and the supporters of it wrote it in a way to bypass federal regulations and control and to create language where no lethal control of wolves would be permitted. Ranchers were prohibited from protecting their property and livestock and had to rely on state employees to attempt to haze wolves from their property. Some livestock losses have already occurred by wolves who made their way into Colorado from Wyoming, and these wolves have even killed and eaten pet dogs near Walden, Colorado.

Warning Signs

In the summer of 2023, wolves had pretty much dropped off the news cycle and out of the public eye. Behind the scenes, plans were being crafted for the capture and reintroduction, but some states such as Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana stated they would not be giving wolves to Colorado. This is of no consequence to those who have crafted the reintroduction plan, and the external hiring of the new director for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Jeff Davis, from the state of Washington, should have been a clue.

Davis was hired to replace former director Dan Prenzlow after a controversial comment by Prenzlow was taken out of context at a public meeting. It’s no secret that most wildlife managers within CPW opposed the wolf reintroduction for decades, so a supportive administrator was brought in from the outside to implement the wolf plan. Davis most likely had friends where he hailed from in the Northwest, as Oregon stepped up to the plate and wolves were promised to Colorado.

Empty Policy

In September of 2023, the federal government was also injected into the state’s business when the US Fish and Wildlife Service published an environmental review of what is called the 10(j) rule. This rule would permit the lethal control of wolves in certain circumstances, such as the protection of livestock. The only caveat is the state agency, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, must approve the issuance of such a permit. At this point, under Governor Polis’s leadership, that has not happened with an application from a North Park Colorado rancher who applied for the permit, and it seems to be a highly unlikely scenario moving forward with the current administration.

Contested Issue

With the looming end-of-2023 reintroduction promise by Polis, legal action seemed imminent. Expectedly, the Colorado Cattleman’s Association and the Gunnison County Stockgrowers Association filed suit in December in a last-ditch effort to stop or slow the release of wolves. A judge ruled quite promptly that the release would go on as planned, and the efforts to stop or even slow the process were nullified. At this point, it appeared unlikely that any efforts would derail the wolf reintroduction process, and speculation ran wild on when and where wolves would hit the ground.

Criteria for the release narrowed the location down to a relatively small area in Colorado that would most likely point toward Eagle County north of Interstate 70 as the prime location. Monday, December 18th will go down in history as the start of a new plan for Western Colorado, as it was the day that five wolves were released near Radium on a State Wildlife Area property.

Backdoor Release

The release was done in relative secrecy with some CPW employees, Governor Jared Polis and his husband, and a few dozen others who are most likely supportive wolf advocates who received invitations for speculative reasons. Not invited nor even notified were local government officials for the counties impacted nor any others not existing in the wolf advocacy echo chamber.

What’s even more astonishing is that some Wildlife Commissioners were not notified of the release, and one of them found out on the evening news. Additionally, Merrit Linke, a Grand County Commissioner who was a member of the Technical Working Group for the Wolf Release, was not invited, even though the releases occurred almost in his backyard and other members were present at the release. These acts speak for themselves and suggest that the only non-CPW people present were ardent supporters of the reintroduction and imply a private-party-like atmosphere to the event.

Coincidentally, there was a “Wolf Update for Livestock Producers” meeting taking place in Craig, Colorado, 70 air miles away from the release site between local ranchers and CPW officials that was hosted by the Colorado State University Extension. Presumably, this was more of an attempt to continue the conversation and foster the working relationship between ranchers and state employees. Partway through this meeting, an announcement was made that five wolves had been released that day. One can only imagine the palpable angst that must have settled over the attendees at that moment.

Fallout Report

As the days progressed, information trickled out about the wolves and the release, most of which begged questions and concerns. Also brought to light were some really poor optics, tactics, and amplification of the existing mistrust in Governor Polis and CPW concerning the process.

Two well-written and informative articles on the release and the wolves were penned by columnist Cat Urbigkit of the Cowboy State Daily and Rachel Gabel of The Fence Post, both detailing missteps, misinformation, and the obvious lack of transparency in the process due to an absence of trust toward the people who call the Western Slope of Colorado home.

The current story is that for this project, 10 wolves were captured in Oregon in December, presumably via net gunning. These were then presumably health-checked and pregnancy-checked (“presumably” is used because of the lack of candid information). What is alarming is that some of the wolves were captured from packs that were involved in and had a history of livestock depredation in Oregon. This information was not released by CPW but instead came from some investigative journalism by Rachel Gabel of The Fence Post.

Cat writes in her online article for the Cowboy State Daily about the release, and anyone reading it can quite clearly see that this was an “at-any-cost” effort by the governor to keep his promise to his supporters and the wolf advocacy contingency. Cat states, “Over the last two years, the message to Colorado livestock producers has been to do all they can to reduce the risk of livestock depredations, and producers have been stepping up to do that. The words ‘conflict minimization’ [are] repeated 176 times in Colorado’s wolf plan. So, when the same agency then takes an action that appears to increase the risk of conflict to livestock producers, what message does that relay?”

When Rachel Gabel blew up the official narrative of the history of the released wolves, Governor Polis’s husband Marlon Reis took to social media the weekend before Christmas and initiated a slander attack for her reporting. Reis deleted some of the Facebook comments he made in short order, but Cat Urbigkit took screenshots of them as evidence of the involvement and demeanor of the First Gentleman of Colorado towards any who question the official narrative or oppose the program of wolf reintroduction that he is heavily involved in.

Vague Information

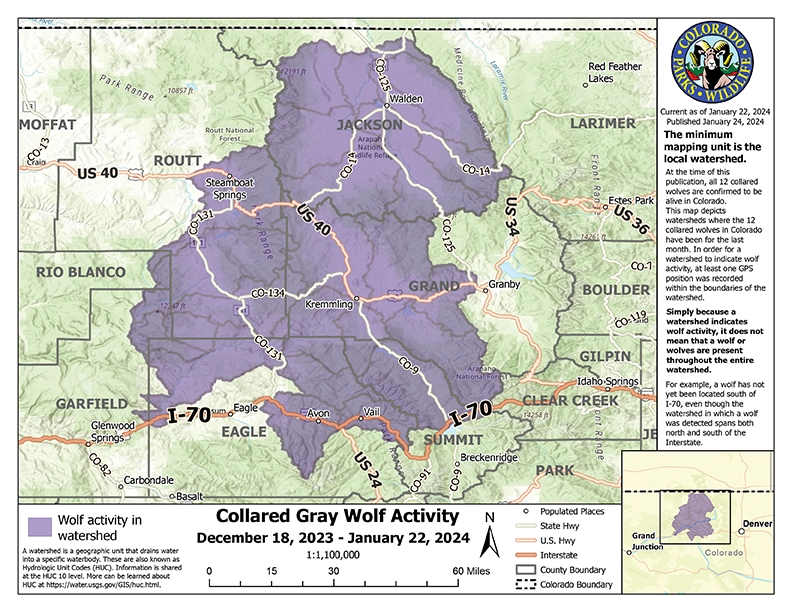

A month later, in January of 2024, all we really have are the anecdotal rumors from social media on wolf locations and an extremely generic map of river drainages where wolves have been, according to radio collar data that was released to the public by CPW. The map shows a large chunk of country with uneven boundaries set by ridgelines and drainage boundaries, but it is essentially from the Continental Divide to near the Utah line and Interstate 70 to the Wyoming border. Zero other information of substance has been released by the state.

There is innuendo in the continued lack of transparency and unwillingness to share wolf radio collar data from the first month of there being paws on the ground. No one has spoken of this with an outside voice, but there is an implication that the wolves need protection from threats. This is mainly generated on social media by some who are very upset by the entire process and consider the wolf reintroduction a threat to lifestyle and financial well-being.

It’s worth noting that none of the wolves that were already present in Colorado have been killed or harmed by livestock growers, even when their livestock and pet dogs were killed. These people oppose wolves on the landscape but respect the rule of law and have chosen instead to fight the battle in the court of public opinion.Simply put, threats against wolves really don’t have much validity at this point. The number of people that would be willing to shoot or harm a wolf and face the full force of both federal and state law enforcement, prosecution, fines and maybe jail time seems to be of no real consequence. So, why the secrecy?

That certainly begs some answers, brings into question the trust of the state towards West Slope residents, and amplifies the distrust of these same people towards the state and CPW. The release appeared rushed, and some may consider it reckless when compared to the care and time taken with the Yellowstone wolf reintroduction. In the case of the CO release, wolves were simply captured, transported, and quickly dumped in locations where no resistance could be given and, seemingly, to meet the deadline and the political promise Polis made to his supporters.

Direct Consequences

A group of five wolves was released in the Radium State Wildlife Area west of Kremmling along the Colorado River, and another pair were released in the Blue River State Wildlife area north of Silverthorne near Green Mountain reservoir. The locations were not publicized but instead confirmed by eyewitness accounts and terrain recognition in the photos and video from the press release.

For bighorn advocates, this release location was extremely concerning, as hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent on a sheep reintroduction program immediately adjacent to the wolf release point, and the herd had grown enough to allow limited permits during the last few years. The sheep were intended to occupy Gore Canyon where the Colorado River cuts through the ridge boundary of Middle Park on the West side but instead, the sheep frequent the open sage and grass hillsides where forage is better and more obtainable.

The sheep would have to react quickly to the presence of wolves and adjust their habitat use to rockier, cliffed-out aspects of the terrain to avoid what could be a total slaughter of the herd if they continued to occupy the open areas away from security. A few weeks after the release, a lone collared wolf was spotted and photographed from the road in the area, in the exact location that the ewe and lamb group in the unit utilizes for winter range. If there was any consideration for the bighorns and the efforts made for their reintroduction, it was obviously deemed less important than the wolf release.

The wolf is not going away in Colorado – much to the dismay of sportsmen and women who see the wolf as a threat and competition to their lifestyle and despite concerns by livestock growers.

Governor Polis will be in office and will be term-limited in three years, but it’s clear that his agenda will be to support and promote the growth of the wolf population in Colorado. There are population goals established, but there is also a high level of distaste and opposition to any sort of wolf hunting or control once those numbers are achieved by those involved in pushing the reintroduction.

Additional Damage

Currently, Northwest Colorado is in the first winter after last year's brutal winter season, during which heavy snow and extended cold temperatures decimated some antelope, deer, and elk populations. Tag numbers were cut drastically, and there is talk of shutting down units to big game hunting due to winter kill losses.

Middle Park, near Kremmling, is a historical deer hunting area that had high populations of animals and offered tremendous hunting opportunity for sportspersons. Due to Chronic Wasting Disease, populations are down, and hunting permits were dramatically increased in an experimental attempt to slow the spread of disease simply by decreasing population density and mature buck representation in the herd. Mature mule deer bucks are considered to be the primary spreaders of CWD because they travel from doe group to doe group while rutting.

Uncertain Future

Wolf populations on the landscape will have an impact in the future, but no one really knows what will happen. What we do know is that other states report heavy impacts from wolves on ungulate populations. Still, some are of the anecdotal opinion that wolves have made some ungulate populations stronger through predation.

Wolves are here in Colorado to stay. That is without question. What will be interesting to see is how they fit in and whether can they stay out of excessive conflict with livestock producers. It is also unknown whether these wolves will reduce deer and elk herds to the point of a reduction of hunting opportunity – not to mention the hunting dollar, which both small-town economies and Colorado Parks and Wildlife rely upon.

A growing urban population on the Front Range of Colorado controls the political direction the state takes. Increasing numbers of people who lack experience and knowledge of the lifestyles and livelihoods of rural Western Colorado residents will probably be the driving force behind wildlife management moving into the future. Consumptive users such as hunters and fishermen are the minorities and must find a place to articulate the value of their way of life to those who get their information from television documentaries and well-funded animal welfare activists who aren’t afraid of using deception to get their way and impose their value sets. It's these challenges hunters must address and push back on if they want the tradition of hunting to survive for future generations.