NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

The Backpack Hunter's Friend - Pack Llamas

Pack Llamas-The Other Four-legged Packers

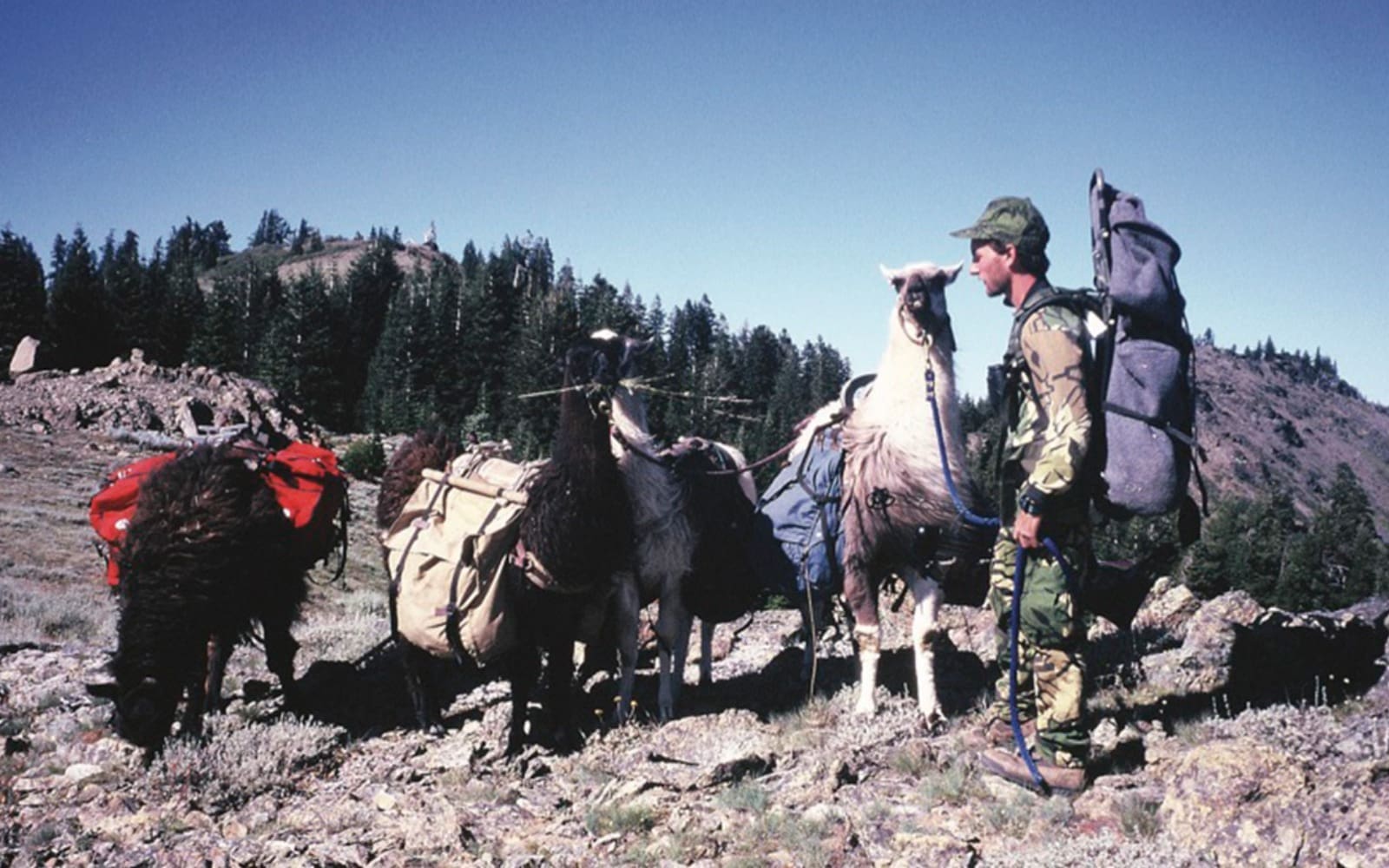

I’ve been backpack hunting since I was 17, and with any luck, I’ll still be doing it when I’m 71. I’m now realizing that I’m just past halfway through those 54 years of enjoying the most spectacular country the West has to offer.

Early on, I didn’t pay a whole lot of attention to the health and longevity of my body. I ate healthy, but I demanded more of it physically than I should have. For 25 years I did construction, mostly working 80-hour weeks, and it prematurely created significant wear on my moving parts. Though my knees and back have recovered a bit since I retired from the trades and took up bow building, I’m acutely aware that I’d now be considered “high mileage” on a used car lot.

For the past five years or so, I’ve been thinking more about how I’ll be able to keep lugging my gear through the mountains. Since there is a shortage of Sherpas in the U.S., the next logical choice is a four-legged packer. A horse or mule is the first animal that comes to mind, but I’ve shared little affinity for them since one tried to eat my hair in first grade. Additionally, they’re expensive to keep, somewhat skittish in nature, and potentially disastrous if things go wrong.

For these reasons, among others, I’ve looked for something more docile, smaller, and potentially less dangerous. Enter the pack llama.

A Crash Course Story

When I was in my teens, one of my neighbors got into llama packing. These creatures intrigued me, and the thought of having something else carry my pack was very appealing, but the price tag was steep.

Fast-forward a decade; the cost of pack llamas had dropped significantly. A lucky find in a local paper and soon I had the start of my own llama herd - an aging male, two youngsters, and a female - none of which had ever packed. We were all in for an education!

Even with limited educational resources, I found it easy to learn how to train them - getting them used to a lead rope, stringing them into a pack train, introducing them to a pack-saddle, loading, and finally packing.

Their life expectancy is 20-25 years and they can be packed into their mid-teens. The older of my llamas was 13-14 when I started packing him - over the hill by packing standards, but he did well until he died at 18.

The ones that did the best for me started packing with a frame and empty panniers at just one year old. They’re too young to carry full weight until about three, but he loaded himself into the trailer, so I took him along as a trainee. He learned quickly from the older pack llamas and the early imprinting made him think it was natural. He ended up being one of my best packers.

Pack llamas are led with a lead rope and halter. Similar to horses, many animals can be led by a single person by tying their lead ropes to the packsaddle of the one in front of them. You’ll find that there is a pecking order and some pack llamas like to be in a certain place in the string. Unless they’re tired, they’ll lead easily and follow you like a shadow.

I used a two-horse trailer for my four pack llamas and eventually graduated to a 12-foot stock trailer when I started packing with six. If you’re going to pack with just two or three animals, they can be loaded into the back of a pickup with stock racks. They’ll lie down once the vehicle starts moving.

Performance

Pack llamas can carry 20-25% of their body weight or 60-100 lbs. I seldom loaded mine that heavy unless I was coming out with meat. I liked to keep their loads at 50-60 lbs., especially with significant elevation gain.

Llamas are native to the Andes Mountains, so if you do your part, they are quite at home in the high elevations and rugged terrain of the Rockies. Still, conditioning plays a big role in how well a llama performs. Leave your llama lounging all year and you’re going to have a pasture potato that will give you fits on the mountain.

If you’re fortunate to live at altitude and have rolling hills for the animals to pasture on, you’ll have little to do to get them ready. I lived just above sea level and my pasture was pancake flat, leaving me more work to keep them in shape. I’ve packed with them in years when I did my due diligence and had a great experience. There were also times I didn’t and I started wondering what llama backstraps tasted like.

Traits and Basic Needs

Llamas have an efficient digestive system, allowing them to thrive on low-protein vegetation. If supplementary feeding is necessary, regular grass hay is fine.

On the trail, they’re entirely self-sufficient, so you won’t have to pack feed. They’re happy eating grass or browsing on leaves. On extended trips, I packed a gallon of grain for a treat at the end of a hard day or if I needed to catch one that got loose.

By nature, they’re more like a cat than a dog, being more aloof. I’ve had a few trips where I wasn’t able to catch a loose llama, so he got to walk out, following his buddies without a pack, but then promptly loaded himself in the trailer at the trailhead. Go figure!

Their hooves are soft like a deer, so they leave little trace. They aren’t destructive to trails or campsites like heavier stock.

Depending on terrain, Pack llamas go 1-½ to 2 mph, which is a comfortable to a slightly slower pace than humans. They don’t have the stamina of a horse, so you won’t be able to put in 20-mile days or do massive elevation gains without a break, but with reasonable discretion, they’ll get the job done.

On the trail, if you encounter other stock animals, it’s good practice to step off the downhill side of the trail to let horses or mules pass. In my experience, mules are particularly freaked out by llamas. As a result, their owners sometimes hold them in disdain. Stepping to the downhill side makes them seem less menacing and could help avoid a rodeo.

At camp, you’ll need to stake them out to graze. I used to bring a 100’ length of rope and tie off each one at intervals.

I took them to water daily, but like a horse, they often won’t drink. Unlike a horse, they can go for several days without water.

The first game animal I loaded on pack llamas was a bear. I was apprehensive when I slung the pannier onto the llama, half expecting a rodeo. Much to my delight, they treated it as any other load. None of the llamas I’ve worked with had a problem with the smell of meat.

Costs

Expect to pay $350-$650 per llama for a complete pack and pannier set. There are a variety of pack designs, but I preferred a rigid frame. Think of it as an internal frame vs. external frame packs. I liked the Sopris packs, but they’re among the most expensive. Panniers need to be loaded equally for balance. A digital luggage scale is perfect for insurance.

Depending on the source, expect to pay $1,000 on the low end for a potential packer and perhaps $2,500- $3,500 for an experienced, trail-proven animal.

You can purchase young, untrained animals, but it’s a good idea to get at least one experienced packer. The younger llamas will learn quickly from the older ones and will fall in line rapidly.

The Perfect Pack Animal?

I don’t want to over-sell llamas as packers. While I feel their virtues certainly outweigh their shortcomings, there are things you need to consider before you dive in and start staking out pasture on the back 40.

Overheating: Llamas don’t do well in hot climates. Packing in the heat of the day can lead to heat stress and even death. A few tips:

- If you’re packing during hot weather, start early, and avoid packing during the hottest part of the day.

- Cut or shear their hair short.

- Cinch the panniers up tightly so that they don’t sag down onto their sides. This will increase air circulation, aiding in cooling.

- Choose a pack frame that is open above the spine rather than one that wraps entirely over the spine.

- Rest them more frequently, especially on climbs, and consider loading them lighter.

Pack llamas do extremely well off-trail, but not well in rockslides. Some have issues crossing water, but I’ve never had a problem training them to eventually accept it. They’ll often have the bad habit of trying to jump smaller creeks, which can wreak havoc on a pack string. They will stop and urinate in water as well.

When they get tired, they’ll lie down. Most of the time I could convince them it wasn’t time to stop, but when extreme measures needed to be taken, a goose between the legs almost always got them to their feet.

While they’re often used as guard animals for sheep, they aren’t invincible. One of my pack llamas was killed by a mountain lion in its pasture.

When they spot something they don’t approve of, they’ll make a loud alarm call. This is the only time you’ll hear them with any kind of volume. On the trail, they’re mostly silent, with the occasional “mMMMmmm” hum that might pass back and forth between them.

Just like horses, you’re going to have to dedicate time to conditioning them. Consider hiking with a loaded pack to get yourself in shape at the same time, but conditioning animals is certainly going to require more of your time.

The cost of feeding them and caring for them is also something to consider. Feed costs are far less than a horse and my vet bills were never big. I trimmed their hooves myself.

To me, the biggest drawback is having an animal in camp that needs to be looked after. You won’t be able to bivy out away from base camp overnight. This just wouldn’t be responsible. If you’re hunting with a buddy, you could take turns bivy hunting away from camp.

The alternative would be to break camp daily and tie off the animals after moving them, but this burns valuable hunting time. No matter what, you’re going to be spending some time taking care of animals. The upside is the gear extra gear didn’t come in on your back, so you’ll be enjoying a more luxurious camp with less effort and the meat haul will be easier.

Do they spit? In a word, yes, but it’s generally to resolve disputes with fellow llamas. A couple of times I got hit in incidental crossfire. Only once did I get a full shot in the face that was clearly intended for me.

Rent a Pack Llama - the Best of Both Worlds?

There are a number of places pack llamas can be rented. I’ve only used rental pack llamas once, but I have friends who have used them multiple times.

My experience was very positive; in fact, maybe better than using my own. These llamas had been used all summer for high country fishing trips, so by September, they were in tiptop shape. Coming from out of state, we were able to rent a trailer from the person as well.

Some offer shuttle service to and from trailheads. Daily rates vary, often giving discounts for more animals or longer duration of use. Rates I’ve seen are $50-$75 per day, including use of packs. I’ve seen weekly fees as low as $100 per animal with a two-animal minimum. This could be an economical way to introduce yourself to packing with llamas before purchasing.

Time to Get Going Again

I eventually sold my animals years ago. I was working out of town, making ownership a challenge. At the same time, I started hunting out of state more and flying to my destination instead of driving.

Now that I’m working from home, things are different. Once again, I’m looking at options for pack animals and llamas will be in the discussion.

In the next blog, I’ll tackle part 2 - pack goats. They provide their own unique attributes and shouldn’t be overlooked. I’ll compare the two and help you decide which animal would better fit your hunting style.

One way or the other, I’ll be reinvesting in a herd of packers and winding back the odometer on my body. Who knows, maybe I’ll be able to push my expiration date to 80?