NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

Sharing the Backcountry: Outfitters vs DIY Hunters

If you spend much time in the backcountry, you’ve likely hunted in areas assigned to outfitters for commercial use by the U.S. Forest Service. Depending upon the national forest and the particular outfitter, your experiences have likely ranged from congenial to contentious. Every outfitter is different and USFS administrators responsible for overseeing the outfitter can range from veteran backcountry rangers who know their region intimately to individuals who are new and know little about their area.

On one hand, there are outfitters who are quite tolerant of DIY hunters. However, there are other situations where regardless of rules and backcountry ethics, jealousy and competition can lead to conflict.

In this article, I’ll share situations that have happened to me. I’ve always believed that we can learn from these experiences, so I’ll share some “best practices” which the DIY horseman can employ to promote shared use and peace and harmony when interacting with outfitters.

My first encounter with an outfitter was in the late 1970s in Idaho’s Clearwater National Forest. At the time, the “Clearwater” was booming with elk as a result of habitat created by past wildfires.

I was new to the area and had just returned to the trailhead after several days of hunting spring black bear. I had stumbled onto an outfitter’s basecamp ten miles from the trailhead where he had a huge salt lick. There must have been 200 cow elk with their calves as well as numerous bulls in small bachelor groups in the basin around his camp. He seemed surprised that I had killed an exceptional black bear and when I told him I had seen “an amazing number” of elk, he gave me “the look”, telegraphing that he wasn’t pleased with me being there.

I soon began hunting elk there. Once I knew where the outfitter’s base camp was located and generally how he hunted the area, I specifically tried to stay out of his way. I established our camp in a remote area three miles from his base camp and four miles from the main trail. We had great success over the next five years and never encountered other hunters, guided or not. The outfitter was disorganized and ran a slip-shod outfit, usually arriving at his camp after we had killed our elk and had left the area.

We also became aware of an individual that was bringing in hunters A.K.A. “friends” from another trailhead and was possibly illegally guiding them. Like the outfitted hunters, we never saw this individual while we were hunting, but we occasionally saw them packing meat.

We usually made a spring trip into the area for black bear and a summer trip to cut firewood and explore. The area was rich with big black bear boars, which were there to hunt elk calves. We felt fortunate to have an area mostly to ourselves with great bear and elk hunting.

Then, in summer of 1982, we noticed a lot of stock use on the main trail. We encountered the individual who had been packing his “friends” into the area. He was trailing a large string of mules, laden with huge loads of “raw” rock salt. I thought he was packing salt for the outfitter, but he informed me that he had just bought the area. I congratulated him. That fall we got our bulls, but never encountered him or his guided hunters.

That fall, the outfitter had one of his guides ride around to every DIY camp located in his permit area and inform them that they had registered a “spike” camp at their location and that they’d have to move elsewhere next fall. Although he had registered a spike camp at my camp location, he chose not to inform us.

I didn’t learn of this tactic until December 1982 when I got a call from a friend in Oregon whose camp was two miles south of us. He told me about the guide coming to his camp and informing him of the spike camp registration. To put it mildly, he was “steamed”. I pondered the situation but didn’t know exactly what to do.

In January, I received a letter from the District Ranger informing me that the basin in which my camp was located was “used by cow elk as a calving area during late May, June, and early July. In order to avoid unnecessary disturbance during this sensitive period, we are curtailing our own activities in the area prior to July 12, and are asking the public to do the same.”

His letter assumed I was a “frequent visitor”. In fact, I usually hunted spring bear there for about five days. Then in August, I usually made a trip to cut firewood.

In the same letter, the Ranger informed me that I had “permanent structures” in my campsite, which were in violation of USFS regulations and I’d have to remove them. I knew our camp had a “developed look” and was exceptionally tidy, but we had a couple hitching rails attached to the trees, so I figured he had reason to ask that they be taken down. The bear hunt closure troubled me, so I decided to research the situation.

In those days (without internet), it was difficult to research various regulations. After a concerted effort and consultation with Idaho Fish and Game, I learned that the USFS didn’t have the authority to restrict such access for bear hunting in elk calving areas. What I did learn was that the outfitter who had attempted to set me up with the Idaho Fish and Game sting had a use permit that restricted use prior to July 12. His USFS grazing permit began on August 1. I suspect the outfitter figured that since he couldn’t access the area until August 1, he didn’t want me accessing the area either.

After I completed my research, I called the Ranger and learned that no USFS employee had ever been to my campsite. In fact, he didn’t know exactly where my camp was located. When I asked him how he knew about my camp, he refused to say. I assumed (correctly) that the outfitter had been to my camp and had made a complaint. I told him that I’d make sure the hitching rails were taken down and stowed standing on end in a nearby tree along with our lodgepole tent poles. I told him as best as I could where my camp was located on a map and he agreed to have his backcountry ranger inspect my camp and advise me of any issues.

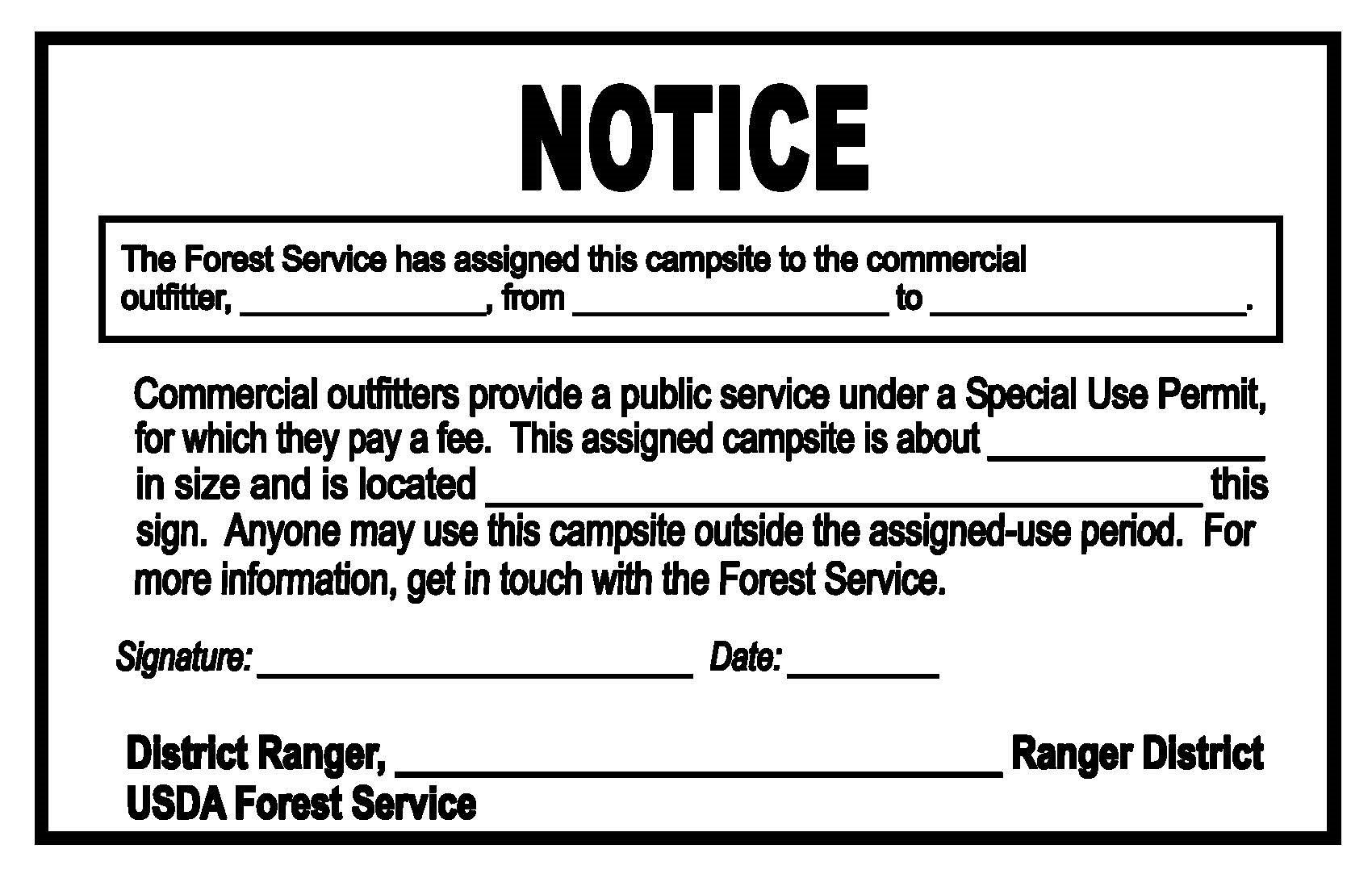

During this call, I inquired about the spike camp situation and he told me the outfitter had indeed registered some new spike camp locations. He noted that the provision for camps in an outfitter guide permit is critical to most outfitters’ operations and that they require exclusive use of these sites. Basecamps and outlying spike camps can be established. When these camps are registered and approved, the USFS provides signage at the site that describes the dates of outfitter exclusive use. There is an annual fee for each assigned site requested by the outfitter. This fee is in addition to the fee for commercial use.

Some spike camps are referred to “progressive camps” and are normal summer operation type camps. They’re usually mentioned on the guide/outfitter annual itinerary, but not assigned. If the site is occupied by the public, the outfitter moves on to the next available site.

In an effort to find a solution, the Ranger suggested that the camp be designated as a progressive camp. When I pointed out that I had used this same campsite since 1977, he suggested that if I got to the camp before the outfitter did, I could camp there, first come, first served. We both knew this was impossible, since the outfitter’s permit allowed him to use the area beginning August 1. With a 14-day restriction on how long I could camp there, it would be impossible for me to “get there first.”

I had to make a trip to Washington D.C. that March, so I planned an extra day to go to the USFS building and spend the day researching guide and outfitter regulations. In short, I had secretaries running all day looking up documents. I returned home with a briefcase full of federal regulations.

Without going into all details, I found quite a number of USFS policies in these documents. After contacting every DIY hunter I knew who was hunting in the area (approximately 25), I advised the Ranger of all of the non-compliance issues we had observed at the outfitter’s various camps.

After more phone calls and letters, the Ranger noted in a letter in April 1983, “I talked with the outfitter about allowing you to use your campsite the first week of the season, after which he would have exclusive use. This was unacceptable to him as he has hunters who want to stay there and he dislikes having you there. I’ve researched the old files to determine if this campsite has been authorized for use by outfitters in the past. Your use of the campsite predates any official outfitter use. Our general policy is to not establish outfitter campsites at locations used by the general public. Therefore, I’m going to remove your campsite from the outfitter’s special use permit.”

After that, I didn’t hear anything more from the Ranger and we continued to hunt the area for another five years. However, in January of the next year, I got a strange call from a hunter in Pennsylvania who said he wanted to hunt with me. I was puzzled by how much he knew about us and our party’s success. I told him that we didn’t invite outsiders to our hunting party. He insisted, so I told him I wasn’t an outfitter and then gave him the new outfitter’s name.

He wasn’t discouraged and called me back a month later offering to send me a catalog from his uncle’s sporting goods store, from which I could order whatever I wanted up to whatever I thought taking him with me was worth.

This was quite strange, and I again told him no. I thought it was over, but mid-summer he called again offering to bring a new horse trailer and “drop it in my yard” with all the necessary papers to register it in my name.

Although I was suspicious, it was then that I “smelled a rat” and told him to never call me again. Five years later at an RMEF banquet-planning committee, the local Idaho game warden introduced himself to me and apologized for the sting operation that they had tried based upon a complaint from the outfitter that I was illegally guiding in his area!

The outfitter continued to generally harass us. After ten years of hunting there, we moved our camp to a new location across the drainage that separated this outfitter and another.

The outfitter in the area turned out to Tony Diebold, a new outfitter from Nevada. We had a great relationship with Tony, helping each other until we moved on to a new area. It was such a pleasure to have such a great guy as Tony guiding where we were hunting. He remains a good friend today and is still guiding in northern Nevada.

As I said, every USFS administrative group is different and every outfitter is different. There are good and bad apples in both barrels. It makes backcountry hunting very enjoyable when you get to work with a good guy like Tony.