NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

A Surprise Mountain Goat Hunt After Major Surgery

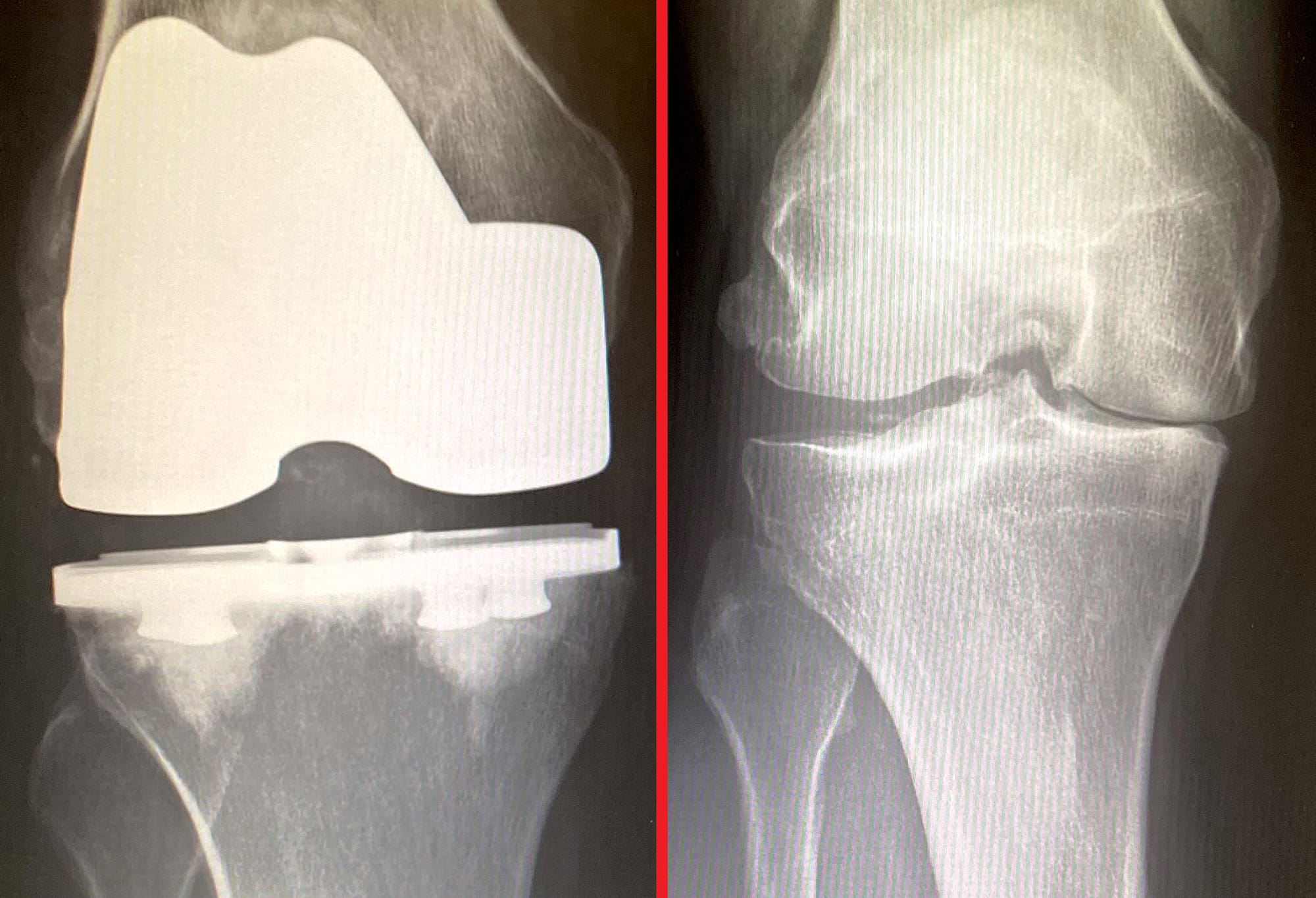

“Bottom line is, you’re going to need a knee replacement at some point,” the orthopedic surgeon told me.

“When do you think I’ll need one?” I asked.

“Oh, you’ll know,” was his answer.

That was spring of 2018 and I had finally gone to the doctor after battling the cycle of hike, ice, rest, and repeat. I consumed ibuprofen, like a kid eating Skittles, in an attempt to manage the soreness and inflammation. My knee was becoming increasingly painful and stiff and would swell up with fluid after the vigorous impact of hiking and downhill skiing.

Lifetime Of Damage

My first injury occurred in my late teens while doing dumb kid stuff. I built a backyard ski jump with an overly aggressive launch angle, resulting in a higher-arch jump and a hard landing. This resulted in a patellar dislocation and possibly some other injuries, unseen. A few years later, I had a fast-break dunk in a men’s league basketball game and was undercut from behind by a guy who thought it was the NBA finals, resulting in another dislocation. I healed quickly as a young man, but my knee was damaged, and cartilage had been torn.

A lifetime of having one knee weaker than the other, hard mountain hunting and compensatory movements took their toll. By the time I was 50, my right knee was pretty worn out. Bone spurs had developed in places of torn and missing cartilage, and I was digressively losing range of motion and experiencing a tightening hamstring. Cortisone shots had lost effectiveness, and the pain in my knee was impacting my quality of life.

In 2020, I struggled through summer conditioning in anticipation of my bucket-list-dream-hunt for a big Dall sheep in the Wrangell Mountains. I was fortunate to experience an early opportunity at a fantastic ram on the second day of the hunt. It was physically challenging for me, but relatively easy by Alaska Dall sheep hunt standards.

Come November, I caught COVID-19 two days before elk season, and this ruled out my mountain hunting for 2020. Living in the spare bedroom for the better part of a week made me even stiffer, and I knew I had a decision to make. The words of the ortho doc seemed to echo in my mind all the time. “Ohhh, you’ll know.” It was that week I decided it was time for surgery.

I experienced a great deal of mental apprehension with the choice to undergo knee replacement. This surgery was a one-way door and there was no going back. If it didn’t work as advertised, my career was over, and my life would be forever changed. Yes, success rates are high for knee replacement surgery, but for 100% success, they are not.

A New Knee

On March 19th of 2021, I lay on an operating room table, cracking jokes and using humor to deflect the stress I felt. Less than two hours later, I was waking up, disoriented somewhat, having zero sense of time passed. Pharmacology was working wonders, I was in no discomfort, and the amazing Dr. Jared Foran told me everything went great, with no complications. By 7 PM that evening, Shellie was pulling our GMC up to the doors of Colorado Ortho Surgery center and I was walking, very gingerly, out the doors of the hospital, just a few hours after having my leg filleted open, bones drilled and sawed upon, and a new, titanium knee joint glued into place.

The next few days involved getting used to doing absolutely nothing but sleeping, resting, and watching Netflix. The pain was manageable with the drug regimen I was given and, in retrospect, doesn’t seem that bad, but I had difficult nights and days with varying levels of discomfort.

Rehabilitation and physical therapy were my complete focus after a couple of days of rest. Pain was omnipresent, but movement and exercise were imperative to limiting the development of excessive scar tissue. I was part of a study for a DIY home physical therapy program, but I also elected to include a few professional appointments a week at our local Axis Physical Therapy in Silverthorne.

I had an app on my phone that gave me exercises, timeframes, and goals for this physical therapy program and I followed it as best as I could, due to my limited range of motion. Inflammation in the joint inhibited my ability to do everything as prescribed, but I pushed through the pain and discomfort as best as I could manage.

I was fairly mobile right away but limited in endurance and range of motion. My first outdoor walk was on a brisk, sunny day in April along the Blue River recreation path in Silverthorne. It was a cloudless, brilliant blue sky, and I looked up at the mountains nearby with a little sadness. At that moment, those peaks seemed so big, so impossibly steep, and strangely distant to me. The mountains I once climbed and adventured in now seemed a formidable fortress I might never again experience. According to the information I read, this feeling of anxiety and frustration was very common for those going through Total Knee Replacement, but it was still very real to me at the time. Managing those feelings was part of having resiliency and part of the healing process.

Progress in rehabilitation was steady for the next couple of months, and though I wasn’t gaining range of motion and strength as fast as I wanted, I continued to improve. By June, I was boarding a United flight to Johannesburg and experienced 18 days in Africa with little problem. By the end of July, I was very mobile and taking our fire department physical ability test to come off of my modified duty assignment. I couldn’t wait to get back to work at the firehouse on a front-line rig. I had the green light from my surgeon to do anything I wanted, within reason, but I still lacked strength and cardiovascular conditioning in my mind. I passed the test and cleared another hurdle in recovery.

Undeniable Opportunity

In the second week of September, I got an email from Colorado Parks and Wildlife stating that someone had turned in a mountain goat tag for the unit I applied for and that I was next on the list to get this tag if I wanted it. Having applied for mountain goat for years and with the uncertainty of future draw possibility, I wasn’t about to turn it down. Unfortunately, the season had already started, I wasn’t in the “mountain tough” shape I thought I needed to be in, and I had a very challenging schedule with multiple commitments. I had a good friend who finally drew a sheep tag after a lifetime of applying and two other good friends with Shiras moose tags, and I had offered to help. My goat hunt would have to wait for a few weeks. This seemed like an OK idea at the time because I really wanted a long-haired mountain goat from the end of the season.

My commitments to friends were eating up the month of September. The Gore Range where I had my goat tag was my backyard, and I am very familiar with these mountains. I knew of some spots to look for goats but had zero time to scout. The stress of missing this opportunity went from omnipresent, low-grade to high-level “holy crap” by the beginning of October, as the season closed on the 7th, and I hadn’t scouted, hunted, or seen a goat yet. I wanted to hunt and take a fully mature billy with my tag and not simply hunt any goat with this either-sex license. Even without the full schedule and last-minute license, my goal had always been to take a long-haired, old billy.

A Promising Lead

On October 1st, I headed up a trail on an alpine ridge in hopes of finding a bull moose for my friend’s daughter who had a permit. No big bulls were seen that day but, what I did see was a curious white dot in a basin where I had a hunch about finding an old billy. I had to move about a mile closer to get details on this white spot that had now moved and affirmed that it indeed was a goat. After setting up my spotting scope, I focused in on this goat who was still close to three miles away. I could make out zero details in horns, but what I did see was what I believed to be a huge-bodied, mature billy, all by himself on a large, pyramid-shaped rock outcropping that made up part of a peak that was well over 13,000’ in elevation.

He looked like a white buffalo with a front-heavy body, high-arching neck above the shoulders, and a long, white beard that accentuated his horse-like head. I am no expert on goats, but I had never seen one that had the “look” this animal possessed. I watched him for just a few minutes as a snow squall enveloped the basin and eliminated the visibility I had, then I began the five-mile hike back to my truck in a driving rain and snow mix.

“Mountain Goat Watch”

Two days later, I was back at the trailhead with my wife Shellie who would help me pack my gear into camp. I had five days left in the season and basically had all these days directed towards taking this goat without any regard to its size or sex. “He” just looked like what I thought and had heard an old billy should look like. At this point, I would have neither the time nor conditioning to hunt another spot.

Three hours later, Shellie and I dumped our packs in a nice little grassy pocket between alpine rock outcroppings at roughly the same elevation I had seen the goat, but at the other end of the basin. I quickly set up the spotting scope and found him within 200 yards of where I had last seen him. It was too late in the day and too far to go after him, plus, my friend Tanner Coulter had volunteered to come help me on the hunt and was going to hike in with his pack at first light.

I kissed my wife goodbye, she set out alone on the long walk back to the 4Runner, and I set up my Kifaru Tarp shelter, rolled out my bag and settled in for an afternoon of “Mountain Goat Watch.” I could make out small dark horns at over two miles distant and see the large dark glands at the base of the horns that are so characteristic of billies. The goat fed and then bedded a couple of times, staying within a small area just below a high alpine saddle at 12,000’. I watched him until dark, then I crawled into my sleeping bag after the old go-to of Mountain House Beef Stroganoff.

Early in the pre-dawn gray light, I could make out the white spot in the spotting scope and was reassured he didn’t move out overnight. I was getting just a little antsy waiting for Tanner when I saw his silhouette crest the ridge a mile distant as he moved with purpose in my direction. I had hoped my wife would have been able to stay, but she simply was too busy with her work and couldn’t take the time away. Seeing Tanner’s smiling face come into camp was a welcome sight.

We discussed the approach and were in full agreement on the route to take. The wind was fickle, typical for the morning in alpine basins, but we had some ground to cover and would fine-tune our approach once we got closer. We circled the basin and dropped into the bottom, planning on going above, behind, and downwind on a long, glacially-carved rock spine. However, when we got to the bottom of the basin, the wind was non-existent. A decision was made for a relatively direct approach, coming in right below, a few hundred yards from where the mountain goat was bedded.

Clear Winner

When we got a little closer, we could now see two billies. This was interesting because a second goat in the basin would have been easy to spot before this. The other billy had probably come over the saddle right above the first goat and joined his friend. Setting up the spotting scope, we could now see that the original billy was between 1/3 to 1/2 body size larger, and while the newcomer was a nice animal, he was obviously not the goat to try and take at this point. The billies bedded again, and we made our way closer, setting up for a shot in some larger boulders at the base of the rocky pyramid the goats were laying upon.

After an hour, the goats got up to feed again, and we could see them moving around on a rock ledge in some stunted spruce. I had to be careful which goat I was going to shoot and positively identify the larger and probably older one.

At this point, we could feel the breeze start to blow uphill as the afternoon sun warmed the air below us and it began to rise. Soon both billies were standing on the edge of a rock ledge, looking downhill, hoping to identify the source of human scent. No goats had been taken in this area in many years, and, most likely, they were just curious hoping to see what they probably thought was another adventurous mountain climber in this rugged range.

I was ready, standing behind a huge pickup-sized boulder with my gun securely nestled onto my backpack and had a clear frontal shot. Whenever possible, I elect to hold out for broadside, double lung shots because an animal will die every single time when shot through both lungs. There was no danger of a serious, damaging fall for the goat. When the large billy turned broadside, I fired. At the shot, the goat dropped almost in his tracks and lurched forward only using his front end. I knew he was spine shot, and when he lurched up again, I sent a second round into his vitals. At that point, brush obscured the goat and we started to make our way up the mountain towards the billy.

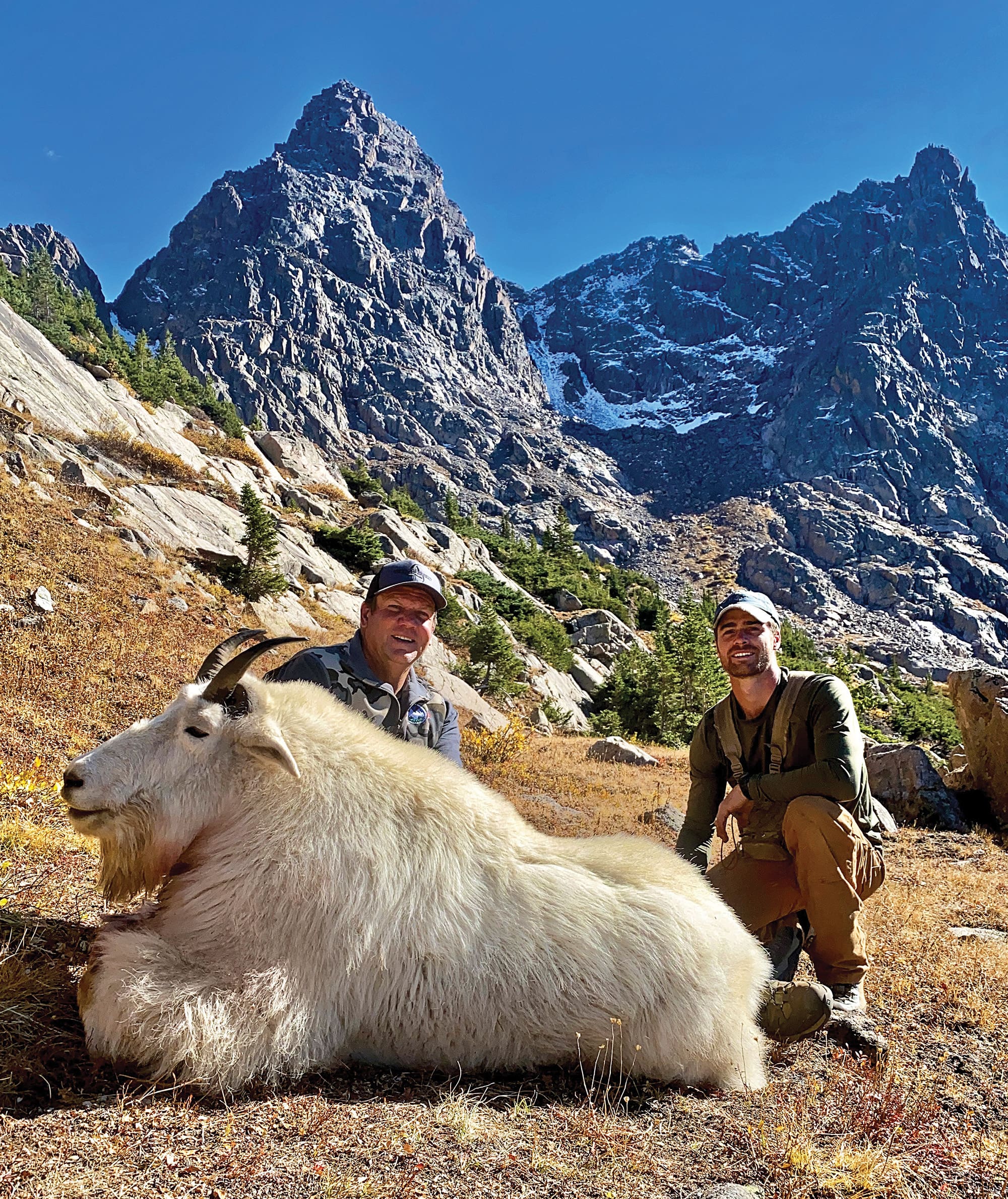

Approaching a giant mound of white hair, Tanner remarked that it was indeed a giant-bodied billy, the largest he had ever seen. That is saying something, as Tanner has guided quite a few mountain goat hunters in Alaska and Colorado. The goat lay in a thick, dead Krummholz bush, and we rolled him off the ledge onto the next bench 20 feet below, as it was way more conducive to skinning and photos.

It was a moment to savor and appreciate. This billy was a collection of superlatives, as he seemed to possess all the qualities a mountain hunter looks for in an animal. The words “majestic,” “awesome,” or “mountain monarch” almost seemed cliché to utter, yet were completely appropriate in describing him. He carried incredibly long winter hair, a huge body, polished black horn tips, and an age that is exceptional for Colorado goats, for he lived 10 years in these mountains. He had survived brutal, cold winters, ferocious snowstorms, and sometimes hurricane-force winds on the rooftop of Colorado, most often living year-round between 11,000’ and 13,000’ in elevation. I felt incredibly fortunate to be given this opportunity.

The long hike back to camp that night with full packs allowed for hours of quiet contemplation and reflection. The rhythmic pounding of footsteps on the trail in the dark and a long uphill grind, always teetering on hyperventilation from exertion, gave me all I could handle at this point. I was still in recovery from my total knee replacement surgery and the months of downtime allowing it to heal, and the mountains had dished out everything that I could handle that day. A headlamp-lit dinner of more dehydrated food was good enough for us that late at night.

With A Little Help From My Friends

I lay in the comfort of my sleeping bag and felt a wave of emotion and gratitude. I was thankful for Tanner helping me as I knew I had bit off a big chunk by killing a goat in this remote basin, eight miles from the trailhead. He is a mountain hunter in the true sense. I was grateful for my wife who had enough of a sense of adventure to help me when I needed it and always backed my play. She helped me, supported me, encouraged me, and even gave me a little tough love when I needed it during rehab. Thanks for keeping my ice machine full, darling.

I thought back to that moment on the rec path by the river in April, then depressed with the idea of never experiencing the mountains on the level I had previously and now felt a sense of gratitude and accomplishment. I had taken both the largest and oldest mountain goat billy out of the Gore Range in many years. This was not easy by most standards and was on the outside edge of my ability at this time, but I did it and felt the rewards associated with goal setting.