NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

A Half-Century of Good Hunting and Lessons Learned in Idaho’s Last Best Place

Research and Good Fortune

It was mid-August 1972 when Tony Dawson and I set out to explore some new country in Idaho which we believed to be a place where big mule deer bucks could be found. It was my first opportunity to hunt big game in Idaho after almost a decade in the U.S. Army and graduate school, and I was eager to explore this exciting new possibility. Tony was in his second year of veterinary school and shared my enthusiasm for big mule deer. In addition, he was as diligent as I in researching whatever fish and game harvest and management information. It wasn’t until the early 1970s when Idaho Fish and Game began assembling data to develop a long-range wildlife-management plan and detailed regional species management plans.

George Dovel was both a fixed-wing and helicopter pilot who had spent decades working with Idaho Fish and Game and had a unique perspective on the significant decline in deer and elk populations state-wide. As part of his advocacy for scientific big game management in 1969-1973, he published The Outdoorsman in newsprint. As a result of his efforts, The Outdoorsman is credited with helping restore scientific game management. In the early 1970s, Idaho made radical changes in hunting opportunity. Archery permits were required for the first time in 1975 by all archers taking part in special archery hunts or separate archery seasons; 6257 archers harvested 252 deer in 1975; 3100 archers took 78 elk. Quotas limiting non-resident deer and elk hunters began in 1972. There were fewer resident deer and elk hunters in 1975 than any year since 1957.

I obtained a copy of The Outdoorsman during the spring of 1972 and was delighted to find mule deer harvest data for several management units in the upper reaches of Hell’s Canyon which straddles the border of Idaho and Oregon. The harvest data for the Hell’s Canyon units was exceptional for mule deer with four or more points. The area was so isolated that many folks did not even know of existence of the plateau sitting in a loop made by the Salmon River where its northerly course swings west to meet the Snake River upriver from Lewiston, Idaho.

I had purchased the USGS 7.5-minute topo maps at their office in Moscow, Idaho and had plotted our route into this area, not knowing just where we might end up. We had basic food, a tarp and sleeping bags & pads. Tony’s mostly rebuilt Toyota Landcruiser was our vehicle of choice, given the remoteness of the area and unknown condition of the gravel/dirt road leading from the Salmon River up to and across the Joseph Plains. We got an early start, and by the time we reached the Salmon River and crossed the only bridge across the Salmon River from where it swings North and West for 87 miles to its confluence with the Snake River, we knew we were in for an adventure. As we began our ascent up the grade on a narrow gravel road, gaining 3,000’ in elevation with 16 hairpin turns, we knew this road was not designed for anyone experienced on driving on treacherous mountain roads.

About half-way to the top of the grade, we pulled off the road at a switchback where we could gaze into the bottom of the canyon more than a thousand feet below. We had decided that this was to be a scouting trip and chose not to overtly “advertise” that we were hunters looking for a place to hunt, discretion being the rule. We had been there for a few minutes when we could see a 1950s-era Ford flatbed truck laboring up the grade below us. It was early in the morning, so we assumed it might be a local rancher. The brakes squealed as the truck ground to a stop just feet from where we were standing. The “cow dog” standing on the flatbed growled and showed us his teeth. Almost simultaneously, the driver growled, “What the hell are you guys doing here? This is all private land and you need to get the hell out of here.”

I politely replied, “We just stopped to stretch our legs and will be moving on shortly.” With a glare that would equal that of a rattlesnake, he put the truck in gear and headed up the grade. Tony and I knew there were some big ranches up here but had no idea of where the property lines might be. Feeling a bit intimidated, we proceeded up the grade, staying our distance behind this not so jolly rancher.

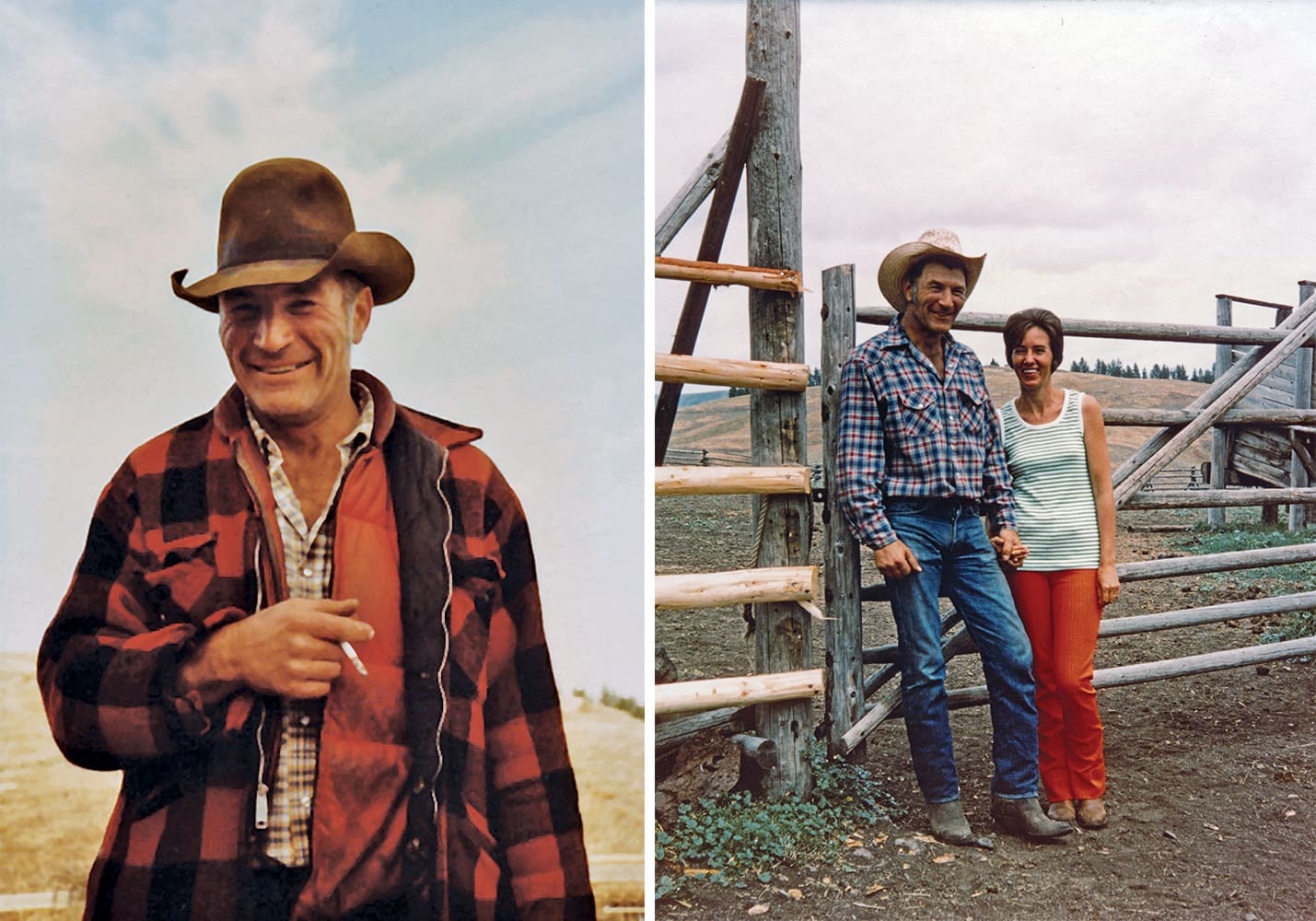

We were about two switchbacks from the top of the grade when Tony spotted a small mule deer buck across the canyon and pulled over on the first wide spot. With Tony intent on looking at with the buck with his binoculars, I suddenly became aware of another vehicle approaching us. It was a brand-new Chevy Blazer. The driver wore a big cowboy hat and had a grin that went from ear to ear. He said, “Hello” as he stepped out of the Blazer and shook my hand. “I’m Cal, and this is my wife, Michele. What are you guys up to so early in the morning in a place like this?” Tony was an enthusiastic amateur photographer and had his “long lens” Canon on a strap around his neck. I replied, “Tony likes to take wildlife photos and we are looking for some mule deer to photograph.”

Cal’s smile broadened and he said, “We have lots of mule deer over at the ranch. I’m the ranch manager on the Spencer Ranch. It is clear out across Joseph Plains overlooking Hell’s Canyon. If you would like to follow us to the ranch, we can see if we can find some mule deer for you after we finish our morning chores. We made a grocery & supplies run to town yesterday and have some hungry critters to take care of first.” Tony and I simply could not believe our good fortune after being scolded for just being parked on the side of the road a few minutes earlier.

As we followed Cal and Michele on the narrow county road, it eventually turned into “ranch roads” and their countless wire gates that wound around on the high ground above the many draws and timbered canyons that drained off to the north, south and west. The bigger drainages had timbered stringers on the north-facing slopes and native bunch grass on the south and west facing slopes that made it a wonderful place for ranching. We wondered about where the mule deer might be. Occasionally there were well-worn “No Trespassing” or “No Hunting” signs on a gate or fence post.

We helped with the afternoon chores and enjoyed a great supper, after which we visited with Cal and Michele about the ranch, the area’s history, and eventually its wildlife. Cal confirmed that there were mostly very large cattle ranches on Joseph Plains, comprising nearly 100,000 acres. Most were operated by managers who took care of the cattle at the “top” pastures and then moved down to the Snake or Salmon Rivers with the cattle for the winter. The grass down by the river, which had not been grazed all summer, was sufficient to maintain most of cattle through the winter. Mail and supplies were delivered by the “mail boat” from Lewiston, Idaho, and at least one ranch had a landing strip along the Salmon River where the mail and supplies were delivered via a Super Cub. It was, indeed, a remote place; so isolated that only the most determined adventurers ever got there, especially in the winter when snow depths prevented nearly all access.

Michele had breakfast ready before daylight, and just as the sun was breaking in the morning, we headed out with Cal to the “breaks.” What was a matter-of-fact morning for Cal was simply unbelievable for Tony and me. The primitive ranch road wound up a brushy draw behind the ranch house and popped out on a huge flat. A half-dozen mule deer bucks were grazing on the flat and bounded off into the breaks of the Snake River as we got near them. Cal simply drove the truck along the rim and stopped periodically for us to walk out to look into the head of one brushy draw after another. Every draw had a mature mule deer buck or two bedded in the shade of the brush, and once they were aware of our presence, they bounded off down the ridge toward the river. It was simply unbelievable!

Cal dropped us there on the rim where you could see the Snake River. We walked all afternoon for miles, glassing into the draws and canyons that coursed down to the Snake River and marveling at the number and size of the bucks that came out of the draws. Needless to say, all of Tony’s photos were of bucks bounding downslope as we never saw them until they spotted us. That afternoon, we thanked Cal and Michele and began our journey home in a quandary of just what to do, knowing we had found an absolute mule deer Mecca, but uncertain as to just how to get access for hunting. As we pondered what to do as we were winding down the grade to the Salmon River, we discussed the topic of just who should take lead on “next steps.” He would be graduating from vet school in two years and unsure of his next destination and I would be living in the area long-term. So, it seemed reasonable for me to lead from that point on.

Reaching Out – Lessons Learned From the Farm

Fifty years ago, I knew nothing about reaching out to strangers seeking permission to hunt on their private land. I thought about what protocols could guide me in seeking permission to hunt in this unbelievable newfound hunting area. Reflecting back on my youth, growing up on our Washington family farm, where each fall mule deer hunters from Seattle would come to hunt our property, I reflected upon how my parents reacted to strangers seeking permission to hunt.

Hunters who asked permission well before the hunting season were usually welcomed each year. We didn’t have “ranch rules” but politeness and simple common-sense practices of not driving in fields, obstructing gates, and being considerate of how and when hunters asked permission seemed to be most important. Deer livers were the most offered post-hunt gifts which my mother accepted enthusiastically. Some hunters gave my brothers and me big Hershey’s chocolate bars, but when a hunter gave my father a box of Peter’s 30-06 ammo, that cemented our relationship with that hunter and his wife for life!

Armed with my experiences on our family farm, I decided to take a thoughtful approach with the goal of building upon our initial visit with Cal and Michele. I wrote them a thank you letter and later called them on their 1950s telephone whose land line was strung from tree to tree and an occasional post in to the ranch from somewhere off toward Whitebird, Idaho. You never knew if they would be able to answer or if the line was down somewhere. During that conversation, Cal and mentioned that he was expecting some school teachers from Grangeville, Idaho, coming to hunt the first week of the season. He said the Spencer family allowed a few hunters who had some association with the ranch to hunt deer, but it was only a handful of individuals.

My call was simply a friendly follow up to my letter and to say hello, so I mostly listened to his updates on the ranch work, cattle, weather, and such. Near the end of the conversation, he asked if we were hunters, being that we were from Washington and out exploring areas in Idaho most people didn’t even know about. I told him I had hunted mule deer on our family farm in Washington. He then told me about a remote area of the ranch where nobody that he knew of had hunted in the past. It was the breaks above where they wintered their yearlings on the gassy benches along the Snake River. He said the country was, “as steep as a cow’s face” and that we could hunt that area if we didn’t mind packing our deer out of the Snake River breaks. He had spent many years in the wilderness, packing for the U.S. Forest Remount facility near Missoula, Montana so I knew he knew how to use USFS maps. I told him I had good, detailed topo maps and asked if I could call him after supper the next night to make sure I had found the correct location.

I pulled out my topo maps of the area, and from his description and the name of the drainage flowing into the Snake River I was able to locate the area which I thought to be the place he referenced. At the time there were no ownership maps available unless you requested them from the county assessor’s office, but he did describe the fence-lines in the area between the Spencer Ranch and two neighboring ranches. When I called him, he confirmed that I had found the correct location. He wished me luck, and I told him I would follow up after the hunt with a letter and perhaps a telephone call.

First Hunt

Tony and I purchased our $135 Idaho Nonresident Bird, Big Game licenses and deer tags at Ward Hardware in Lewiston, Idaho. With our licenses in hand, all we had to do was get our gear together and make a plan for opening day of Idaho’s deer season. In those days, we never thought of wearing camo and made do with what we had. I had a few items I had purchased at one of the annual winter sales held at the Eddie Bauer store in Seattle, WA, which I added to leftover Army gear.

We decided to drive into the area the day before opening morning so we could get our bearings and compare the topo maps to the actual terrain. We followed the primitive road Cal had described that led across the rim of the breaks off the main road to a saddle at the top of the breaks where we could see all the way to the Snake River. It was evident that no vehicles had been here all summer, so we knew this spot was indeed remote. We warmed up our pre-made supper and sat on the edge of the rim, making as little noise as possible, glassing for deer until it got dark. Neither of us slept much that night, and we were up before daylight.

Instant oatmeal, Carnation Instant Breakfast and coffee warmed over a can of Sterno made for a quick breakfast. Lunch would be salami, cheese, crackers, sardines, Snickers bars, and an orange. It was a warm, sunny day so we carried several Nalgene containers of water. I had my topo map, 7x Navy surplus binoculars, Marble’s knife, nylon cord, and two halves of a mattress cover for meat bags. I had backpacked elk quarters on my REI pack frame on our farm, but had never thought about backpacking a mule deer. A Pendleton wool shirt, Eddie Bauer down vest and hat, and my U.S. Army issue heavy wool shirt complimented my Wrangler jeans. My prized .240 Weatherby, topped with a Redfield “rangefinder” 3-9x scope, completed my gear list. Lunch, water and essentials were stowed in an Army issue rucksack which was strapped to my REI pack frame. I was 30 years old and had been hunting chukars in the river breaks below Lewiston, Idaho, for a month, so I felt up to the task of getting a deer out of the breaks if I was fortunate to find a “good one.”

Tony was anxious to get going, and we almost stumbled upon two mature four-point mule deer bucks less than a quarter-mile from our camp. Either one would have been a real trophy and the biggest mule deer I had ever seen while hunting. Tony was an adamant disciple of the Boone and Crockett scoring system and was constantly throwing B&C scores around the time we jumped a buck on our summer trip to the ranch. I knew very little about B&C scores, and a nice mature 4x4 would have been just fine for me. He immediately said, “They aren’t big enough,” as I dropped into a sitting position. He was so adamant and talking so loudly that the bucks sprinted off down the ridge into the breaks. He scolded me for not waiting for a buck that would score high under the B&C system.

When you are hunting with someone whom you do not know very well, there are basic ethical protocols and considerations for your hunting partner(s) that generally apply, especially when two hunters are seeking “trophy” animals and hunting together. I was surprised by the scolding and told Tony that I simply wanted a 4x4 mule deer and B&C didn’t matter to me. He then informed me of his “rule” for two hunters hunting together that the person who spots an animal first has the choice of stalking that animal or “passing” it on to his hunting partner. During my previous hunting experiences with others, we were both just as excited with our partner’s success as we would have been with our own. Puzzled by this new rule, I decided there would be enough bucks for both of us and let him run “lead dog.”

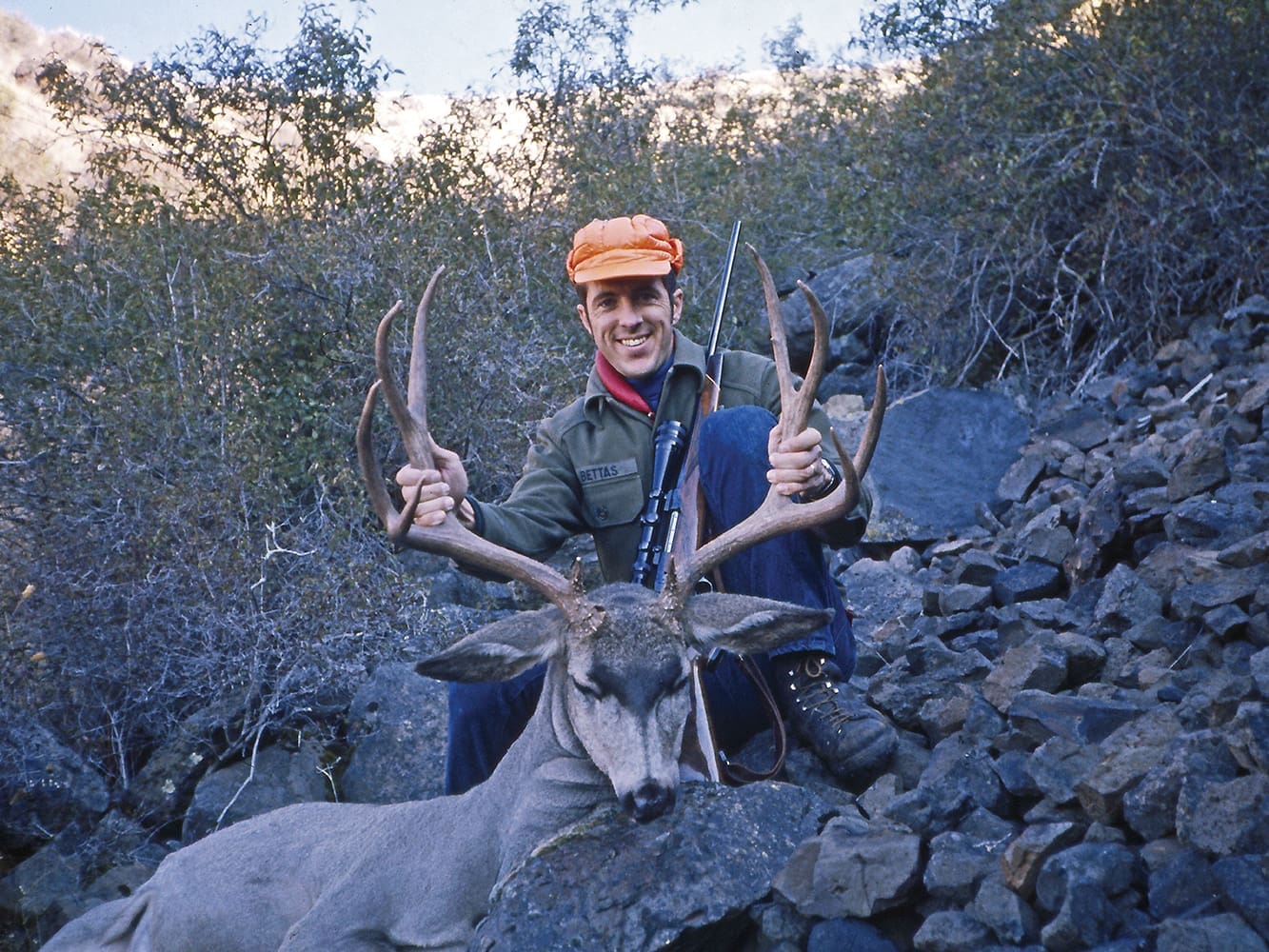

We proceeded around the rim, glassing into the canyons below, Tony always out in the lead and me trailing behind, wondering about this “rule.” It was a stunningly beautiful day, and I was simply enjoying the scenic beauty of the canyons and brushy draws. We had gone about a half-mile and came to the ridge above a deep, brushy canyon leading down to the Snake River. When we got to where we could see across and into the canyon, we approached with as much stealth as possible so as not to skyline ourselves. Tony’s glasses were focused on the opposite side of the canyon, so I looked down into the bottom of the canyon. There, browsing in the shade, was a magnificent mule deer buck. I didn’t say anything and laid my pack frame and rucksack on the basalt rock in front of me and immediately had the buck in my scope, less than 200 yards. I whispered, “Be quiet, I’m going to shoot this buck.” Tony saw the buck I had referenced and immediately started talking, “He’s wide but not tall enough, and the points are not long enough.” The buck was now aware of our presence and looked up our way. I pulled the trigger and the .240 Weatherby with a 95-grain Nosler partition did its job.

As we made our way down the brushy, rocky slope, Tony kept admonishing that I should have waited. As we reached the buck, the concept of “ground shrink” didn’t apply, and Tony got very quiet. Later, he “green scored” it just short of 180 B&C.

Lessons Learned

Before you choose to hunt with someone, spend time understanding their ethical and other hunting practices and expectations. Safety comes first, followed by ethics and unsaid practices which have been handed down through families or simply personal “rules.” I was able to hunt with Tony under his “first to spot gets to choose” rule for two additional years. However, since I was always in much better physical shape than he was and a better hunter, I was the one who got the biggest deer or elk on our outings. This led to jealousy, which will ruin even the best friendship or relationship.