NOTICE: Certain links on this post may earn a commission for Western Hunter Magazine from Amazon or our other affiliate partners when you make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

Spring Bear Hunting in Elk Calving Areas

I began hunting black bear in 1972 in Idaho’s Clearwater Region, primarily in the Lochsa and Kelly Creek drainages. My previous experiences with hunting black bear were more related to an occasional black bear sighting in the fall while hunting deer or elk rather than specifically focusing upon bear. Hunting bear during the spring was also a new endeavor for me.

I was introduced to spring bear hunting by a young veterinary student at Washington State University. I was impressed by his enthusiasm for hunting, especially spring black bear hunting.

Black bear season opened in Idaho on April 15 and the Lochsa River was easily accessible via Highway 12, which had opened a decade earlier, providing a route through the rugged Selway-Bitterroot Range to Missoula, Montana. The country was majestic, rugged, and remote enough that it wasn’t difficult to see a lot of bears.

In those days, you didn’t need much more than a car camping outfit. The hunting technique was just as simple, as one could simply drive up and down the highway looking for bears along the river. The most significant challenge was crossing the Lochsa River if you were unlucky enough to shoot a bear across the river.

As luck would have it, my friend shot a bear on a basalt outcropping high above the river. As a result, we went searching for a boat that we could borrow and transport up the highway to the kill site with his VW Beetle. We finally retrieved the bear, but I wasn’t excited about the “road hunting” technique and was even less enamored with crossing the Lochsa at high water.

Although my first spring bear hunt didn’t measure up to my idea of a quality hunting experience, I was hooked on the idea of hunting spring bear. A couple of weeks later, I found an experienced backpack hunter who was as interested as I was in getting into the backcountry away from the highway and the river.

We were both new to black bear hunting and were eager to learn more. As a result, we hunted together for nearly a decade. For me, it was the beginning of more than 40 years of searching for black bears in the high country of Idaho and Montana.

A Convergence

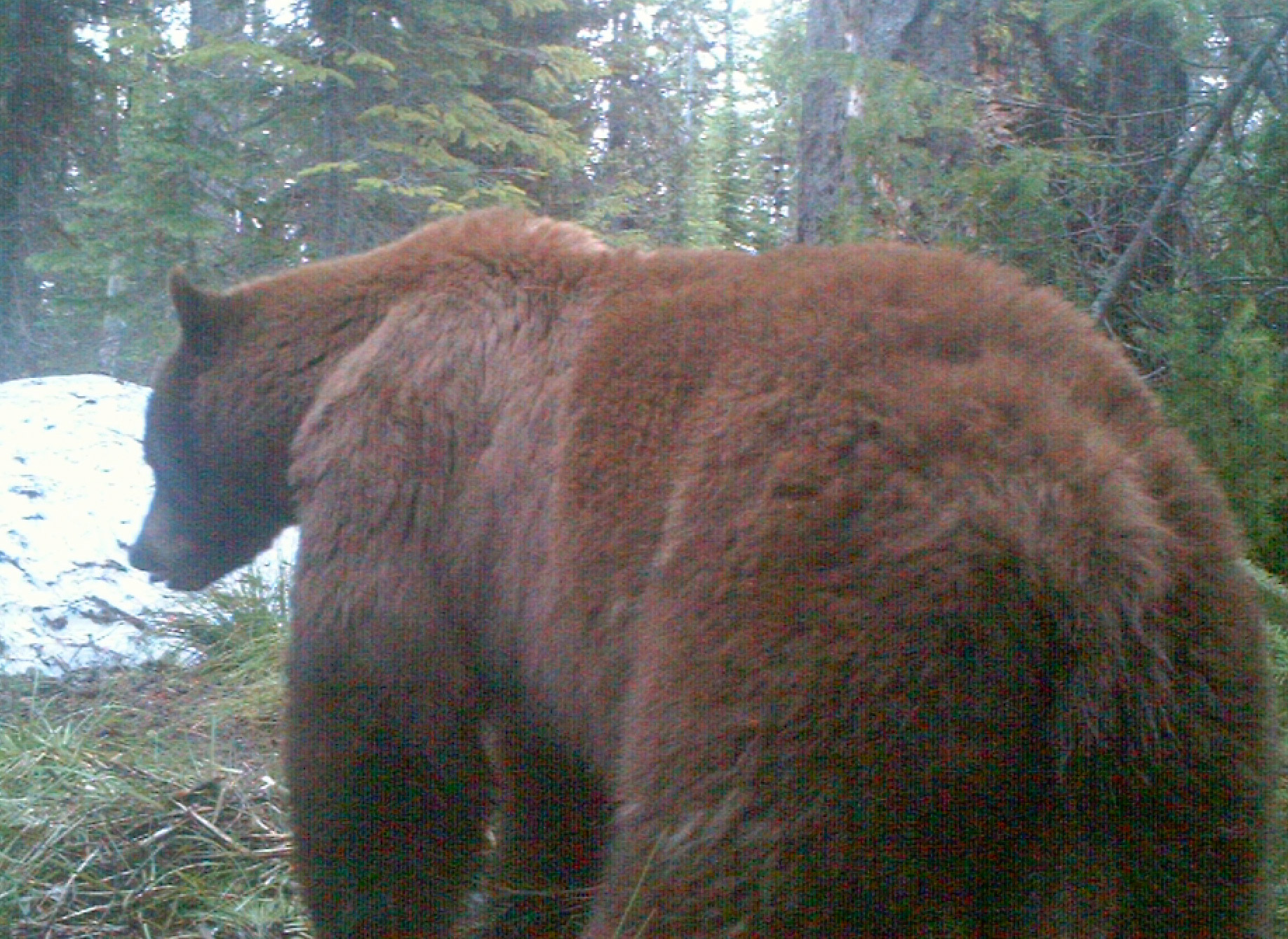

During late April, bears were easy to find along the Lochsa, Clearwater, and Selway Rivers. The bears typically move to lower elevations in search of food after emerging from their dens. In addition, much of that area had a preponderance of adult bears, since it was pretty much an unhunted population due to its remote, rugged mountains with almost no road access.

As the snowline receded, the bears followed the snowline searching for the new green shoots of grasses, forbs, and other foods uncovered by the newly melting snow. By late May, the bears were concentrated in the seeps, wet meadows, and open areas at elevations well above the river bottoms.

Backpacking into these areas put us right in the middle of the large elk herds that were also following the snowline to the open meadows and brush fields found at the higher elevations. As we hunted these areas, we encountered large “nursery herds” of cow elk with their calves. We were also finding large male black bears in these same areas.

Note: Idaho’s Clearwater National Forest was once home to the nation's largest elk herd. As a result, this was a premier elk hunting area. Elk are a product of disturbance and they thrive where fire has disturbed a forest. The Clearwater was where, in 1910, three million acres of forest burned in just two days! That fire and the fires of 1919 and 1934 created huge brush fields and open spaces where red-stemmed ceanothus thrived. Ceanothus is a very desirable elk food, resulting in a thriving Clearwater elk herd.

We seldom ever encountered other bear hunters in these remote areas. Most spring bear hunters had taken bears at much lower elevations earlier in the spring.

Since we were hunting large boars, we looked over many bears each spring. By late May/early June, we usually had one bear tag left between us.

Because bears are omnivorous and typically have access to a wide range of foods, I never gave much thought to them also being opportunistic predators. I had always found bears where the spring green-up was fresh or where they were feeding on winterkilled carcasses. It didn’t dawn on me then that there was a relationship between the bears and the elk.

The More You Know…

Nearly all mortality among elk calves occurs during the first few weeks of life. This is the time when calves are most vulnerable to bear predation.

In 1973, while I was hunting bear in the Selway, I met Idaho research biologist, Mike Schlegel, who was doing a major study on neonatal calf survival and cause-specific mortality in the area. Although elk populations were on the increase throughout Idaho at the time, concern over elk calf recruitment in the Lochsa and Clearwater had led to Schlegel’s study.

Since I had also begun packing into these same areas while hunting elk, I was particularly interested in Mike’s work. As a result, I spent considerable time over the next several years visiting with Mike. This research is interesting and could be the subject of another major article, but in short, the study results demonstrated that one major mortality factor was predation - primarily black bear - with 80% of the predation occurring within a two-week period, May 30 - June 14. This period coincided with when the majority of the elk calves are born in the area.

The reason we were finding elk and bears in the same locations on the spring range was because they were there for basically for the same purpose - spring green-up. They were both following the snow line up and overlapping. As opportunistic predators, bears were finding and killing newborn elk calves.

This study and a similar study replicated in the area later indicated bears were killing more than half of the elk calves each year. Similar research throughout the western U.S. and Alaska has found similar results in that bears, both black and grizzly, prey upon newborn ungulates.

In addition to understanding the dynamics of bear predation on elk calves due to forest succession and habitat reasons, I also learned that bear predation on elk calves can be a learned behavior. This is especially true among mature boars, which tend to frequent elk calving areas.

In addition to capturing and monitoring elk calves during this study, bears were also trapped, monitored, and relocated. As a result, researchers recorded sightings of bears, some of which I found particularly interesting. Although aerial monitoring of elk occurred during most daylight hours, more than 70% of black bear sightings were between 4 p.m. and dark. The next most frequent sightings were daylight to 10 a.m.

The info I learned during my first five years of hunting spring bears and the data from Mike Schlegel’s studies have not only shaped my bear hunting strategies for nearly 40 years but have also contributed to many successful treks for myself and my hunting companions into the mountain ranges of northern Idaho and most of Montana.

I began hunting spring bears in Montana in 1980 and have continued hunting nearly every year since then. Although I’ve hunted during various stages of the spring green-up, my most favorite treks into Montana’s bear country have been during the first two weeks of June, when the elk are calving in the high country and big boars are on the prowl, looking for newborn elk calves.

Spring Bear Locations

The greatest density of Montana black bears is found in the Seeley-Swan region, as well as the Kalispell region. I’ve hunted that area occasionally, but my favorite areas are the Madison Range, Big Snowy Mountains, Crazy Mountains, and the Snowcrest and Gravelly Ranges. Depending upon spring green-up, you can find bears in all of these areas at lower elevations by the April 15 opener.

My preference is to wait until June and get into elk calving areas away from road systems. You’ll find yourself mostly alone, with only the company of deer, elk, and bears, both black and grizzlies these days.

Techniques

My basic rule for spring bear hunting is to be in a location where I can glass a considerable amount of country between 4 p.m. and dark. On occasion, I’ll encounter hunters in their camp getting supper by 6 p.m., missing primetime!

I use early morning and midday hours to reach key glassing areas. When backpack hunting, I like to hunt through the country, looking for elk, bear habitat, and especially calving areas, camping wherever darkness finds me, usually in a high basin or plateau where bears will be visible.

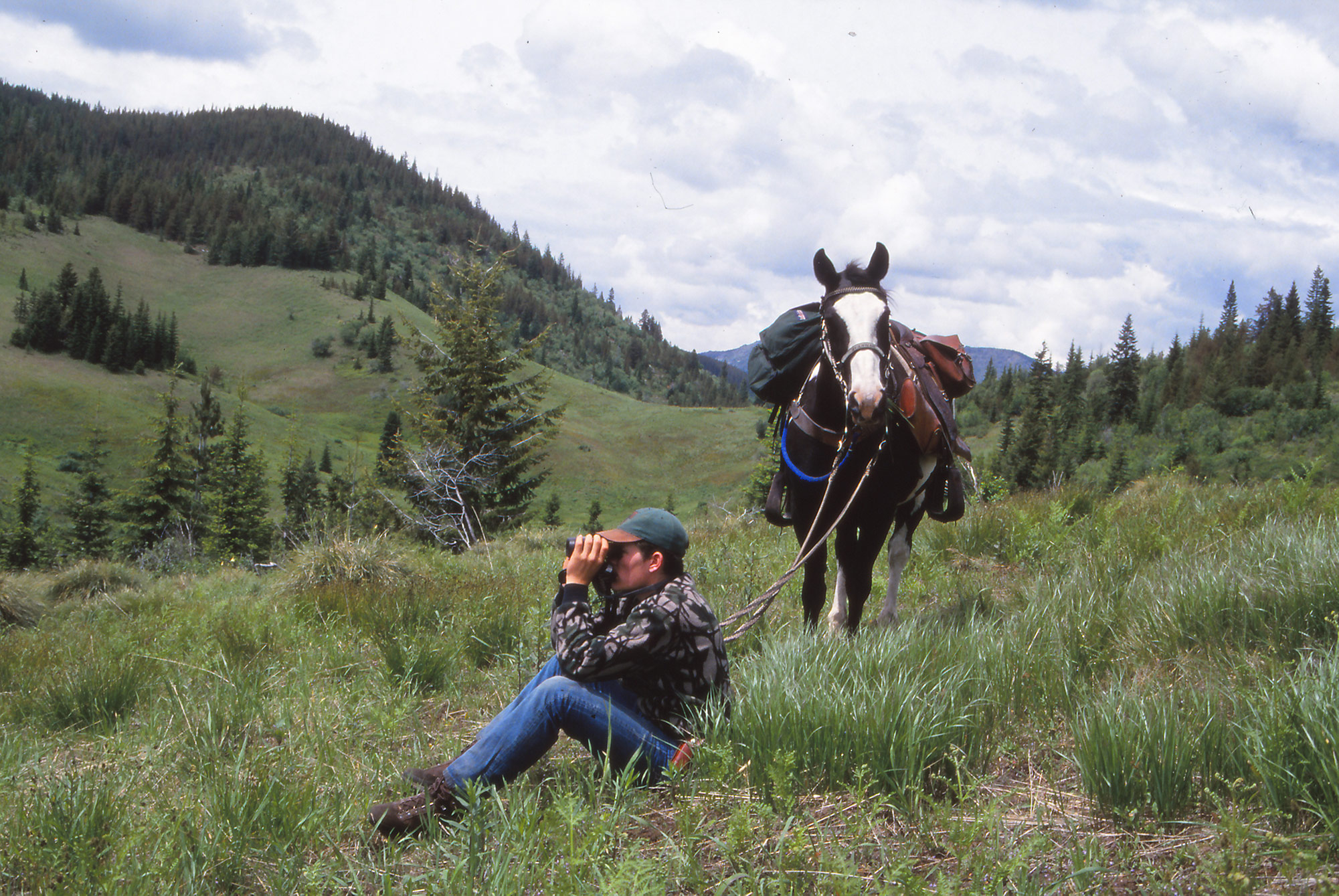

The other horseback technique I like is to hunt from a campsite from which I can ride considerable distances into the backcountry during the morning and then return to camp, usually well after dark.

Using these strategies, I seldom do much hunting in the mornings. Late dinners at midnight aren’t conducive to getting on the trail at daylight like I would in the fall while deer or elk hunting.

What to Look For

Montana’s mountain ranges and related elk habitat tend to be drier than northern Idaho, and elk aren’t forced into the same kinds of open areas among highly timbered areas. Thus, Montana’s elk calve in different habitat types. In some areas, Montana‘s elk calve at much lower elevations, where bears may not be as prevalent. Finding elk calving areas in Montana requires “boots on the ground”.

When you find an area where cow elk are located during the first two weeks of June, you likely have found a calving area. You may find larger nursery herds, but I’ve found that Montana’s backcountry elk can be much more disbursed when they calve. Perhaps wolves on the landscape may have something to do with this observation.

Once you find elk calving areas, make a note, as you’ll be able to return annually. Bears will be there, possibly both black and grizzly in many areas. As a responsible bear hunter, you must know how to identify a black bear vs. a grizzly.

Bear Sign

Bear sign isn’t difficult to find, as they’ll often use game trails and ridgelines to travel. Tracks in the mud are easily identifiable, and if you’re observant, you can find where they walk through fresh grass along creeks and elsewhere. Scat is also prevalent where bears are frequenting wet areas with new grasses. Meadows with lush green grasses are good places to look just below the snowline.

Rocky outcroppings often gather the sun’s heat. Thus, some of the earliest growth of new grasses and forbs will be found on south-facing sides of such rock formations.

In calving areas where a bear has killed a calf, you’ll often find the remains of the kill. When a black bear kills a calf, nearly all of it will be consumed except the legs, skin, and skull. If you find the kill site before coyotes or other scavengers disturb it, it will often look as if it has been skinned. On the other hand, a grizzly bear will consume the entire calf, including legs, hooves, etc.

Spot and Stalk

Spotting a black bear is one thing. Getting to it in time is another. I’ve had some interesting “races” that have left me out well after dark hiking back to my horses or my camp. It’s easy to cover a lot of ground while focused upon the bear. In such situations, one needs to pay attention to the landscape and key landmarks for the return journey. Modern-day GPS simplifies this process. In the “old days”, we hiked a lot in the dark using only our innate sense of direction and the landmarks we had noted along the way.

Of course the first word in “spot and stalk” is “spot”. Since I like to glass from high points late in the day, excellent optics are essential!

Bears feeding in grassy areas will sometimes move from a grazing area and then return to feed again in the same area. This is common with a good food source. If you’re stalking a bear and this happens, it’s worth your effort to watch the area until you’re sure the bear has moved on. I’ve often “sat” on such areas until the end of shooting light and had the bear return at last light.

Although I hunted bears in Montana before I moved to the Bitterroot Valley in 2002, spring bear hunting on Montana’s elk calving areas has become an occasion which I look forward to annually. For me, it’s a great way to introduce new, young hunters to bear hunting in some of Montana’s finest wild, scenic backcountry places!

Regardless of how you choose to get into the backcountry of Montana or Idaho, stalking spring bears is an opportunity for a great adventure where you’ll see all sorts of wildlife. If you can find and hunt an elk calving area, you just may be rewarded with a bear of a lifetime!